Wikipedians voted overwhelmingly against kryptonite — for using Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) as the main content license for Wikipedias and their sibling projects, permitting these to incorporate work offered under CC BY-SA, the main non-software copyleft license used outside of Wikipedia, and other CC BY-SA licensed projects to incorporate content from Wikipedia. The addition of CC BY-SA to Wikimedia sites should happen in late June and there is an outreach effort to encourage non-Wikimedia wikis under the Free Documentation License (FDL; usually chosen for Wikipedia compatibility) to also migrate to CC BY-SA by August 1.

This change clearly ought to over time increase the proportion of content licensed under free-as-in-freedom copyleft licenses. More content licensed under a single or interoperable copyleft licenses increases the reasons to cooperate with that regime — to offer new work under the dominant copyleft license (in the non-software case, now unambiguously CC BY-SA) in order to have access to content under that regime — and decreases the reasons to avoid copylefted work, one of which is the impossibility of incorporating works under multiple and incompatible copyleft licenses (when relying on the permissions of those licenses, modulo fair use). Put another way, the unified mass and thus gravitational pull of the copylefted content body is about to increase substantially.

Sounds good — but what can we expect from the actual impact of making legally interoperable the mass of Free Culture and its exemplar, Wikipedia? How can we gauge that impact, short of access to a universe where Wikipedians reject CC BY-SA? A few ideas:

(1) Wikimedia projects will be dual licensed after the addition of CC BY-SA — content will continue to be available under the FDL, until CC BY-SA content is mixed in, at which point the article or other work in question is only available under CC BY-SA. One measure of the licensing change’s direct impact on Wikimedia projects would be the number and proportion of CC BY-SA-only articles over time, assuming an effort to keep track.

I suspect it will take a long time (years?) for a non-negligible proportion of Wikipedia articles to be CC BY-SA-only, i.e., to have directly incorporated external CC BY-SA content. However, although most direct, this is probably the least significant impact of the change, and my suspicion could be upset if other impacts (below) turn out to be large, creating lots of CC BY-SA content useful for incorporating into Wikipedia articles.

(2) Content from Wikipedias and other Wikimedia projects could be incorporated in non-Wikimedia projects more. The difficulty here is measurement, but given academic interest in Wikipedia and the web generally, it wouldn’t be surprising to see the requisite data sets (historical and ongoing) and expertise brought together to analyze the use of Wikimedia project content elsewhere over time. Note that a larger than expected (there’s the rub) increase in such use could be the result of CC BY-SA being more straightforward for users than the FDL (indeed, a major reason for the change) as much or more than the result of license interoperability.

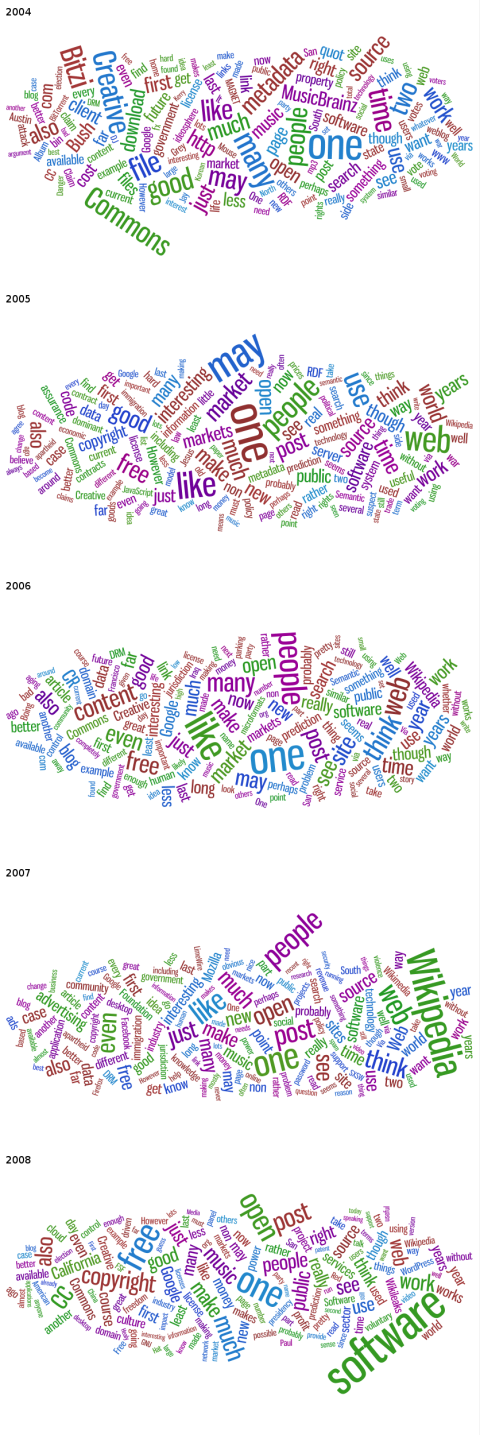

(3) New and existing projects could adopt or switch to CC BY-SA when they otherwise wouldn’t have in order to gain compatibility with Wikimedia projects. One sure indication of this would involve major projects using a CC license with a “noncommercial” term switching to CC BY-SA and giving interoperability with Wikipedia as the reason for the switch. Another indicator would simply be an increase in the use of CC BY-SA (and even more permissive instruments such as CC BY and CC0, to the extent the motivation is primarily to create content that can be used in Wikipedia rather than to use content from Wikipedia) relative to more restrictive (and non-interoperable with Wikipedia) licenses.

(4) Apart from needing to be compatible with Wikipedia because one desires to incorporate its content, one might want to be compatible with Wikipedia because it is “cool” to be so. I don’t know that this has occurred on a significant scale to this date, so if it begins to one possible factor in such a development would be the change to CC BY-SA. How could this be? As cool as Wikipedia compatibility sounds, having to adopt a hard to understand license intended for software documentation (the FDL) makes attaining this coolness seem infeasible. Consideration of the FDL just hasn’t been on the radar of many outside of the spaces of documentation, encyclopedias, and perhaps educational materials, while consideration and oftentimes use of CC licenses is active in many segments. However, in most of these more restrictive CC licenses (i.e., those prohibiting commercial use or adaptation) are most popular. So if we see an upsurge in the use of CC BY-SA for popular culture works (music, film) the beginning of which coincides with the Wikimedia licensing change, it may not be unreasonable to guess that the latter caused the former.

(5) The weight of Wikipedia and relative accessibility of CC BY-SA could further consensus that the freedoms demanded by Wikimedia projects are some combination of “good”, “correct”, “moral”, and “necessary” — if some of these can be distinguished from “cool”. In the long term, this could be indicated by the sidelining of terms for content that do not qualify as free and open, as they have been for software, where shareware and similar obvious competitors for important free software niches are strategically irrelevant.

Obviously 3, 4, and 5 overlap somewhat.

(6) I conjecture that making more cultural production more wiki-like (or to gain WikiNature) is probably the biggest determinant of the success of Free Culture. More interplay between the Wikipedia, both the most significant free culture project and the most significant wiki, and the rest of the free culture and open content universe can only further this trend — though I have no idea how to measure the possible impact of the licensing change here, and wouldn’t want to ascribe too much weight to it.

(7) Last, the attention of the Wikipedia community ought to have a positive impact on the quality of future versions of Creative Commons licenses (there shouldn’t be another version until 2011 or so, and hopefully there won’t be another version after that for much longer). Presumably Wikipedians also would have had a positive impact on future versions of the FDL, but arguably less so given the Free Software Foundation’s (excellent) focus on software freedom.

Will any of the above play out in a significant way? How much will it be reasonable to attribute to the license change? Will researchers bother to find out? Here’s to hoping!

…

Prior to the Wikipedia community vote on adopting CC BY-SA it crossed my mind to set up several play money prediction market contracts concerning the above outcomes conditioned on Wikipedia adopting CC BY-SA by August 1, 2009, for which I did set up a contract. It is just as well that I didn’t — or rather if I had, I would have had to heavily promote all of the contracts in order to stimulate any play trading — the basic adoption contract at this point hasn’t budged from 56% since the vote results were announced, which means nobody is paying attention to the contract on Hubdub.