Last month the Free Software Foundation and Software Freedom Conservancy launched copyleft.org, “a collaborative project to create and disseminate useful information, tutorial material, and new policy ideas regarding all forms of copyleft licensing.” The main feature of the project now is a 157 page tutorial on the GPL which assembles material developed over the past 10 years and a new case study. I agreed to write a first draft of material covering CC-BY-SA, the copyleft license most widely used for non-software works. My quote in the announcement: “I’m glad to bring my knowledge about the Creative Commons copyleft licenses as a contribution to improve further this excellent tutorial text, and I hope that copyleft.org as a whole can more generally become a central location to collect interesting ideas about copyleft policy.”

Last month the Free Software Foundation and Software Freedom Conservancy launched copyleft.org, “a collaborative project to create and disseminate useful information, tutorial material, and new policy ideas regarding all forms of copyleft licensing.” The main feature of the project now is a 157 page tutorial on the GPL which assembles material developed over the past 10 years and a new case study. I agreed to write a first draft of material covering CC-BY-SA, the copyleft license most widely used for non-software works. My quote in the announcement: “I’m glad to bring my knowledge about the Creative Commons copyleft licenses as a contribution to improve further this excellent tutorial text, and I hope that copyleft.org as a whole can more generally become a central location to collect interesting ideas about copyleft policy.”

I tend to offer apologia to copyleft detractors and criticism to copyleft advocates, and cheer whatever improvements to copyleft licenses can be mustered (I hope to eventually write a cheery post about the recent compatibility of CC-BY-SA and the Free Art License), but I’m far more interested in copyleft licenses as prototypes for non-copyright policy.

For now, below is that first draft. It mostly stands alone, but might be merged in pieces as the tutorial is restructured to integrate material about non-GPL and non-software copyleft licenses. Your patches and total rewrites welcome!

Detailed Analysis of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike Licenses

This tutorial gives a comprehensive explanation of the most popular free-as-in-freedom copyright licenses for non-software works, the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (“CC-BY-SA”, or sometimes just “BY-SA”) – with an emphasis on the current version 4.0 (“CC-BY-SA-4.0”).

Upon completion of this part of the tutorial, readers can expect to have learned the following:

- The history and role of copyleft licenses for non-software works.

- The differences between the GPL and CC-BY-SA, especially with respect to copyleft policy.

- The basic differences between CC-BY-SA versions 1.0, 2.0, 2.5, and 4.0.

- An understanding of how CC-BY-SA-4.0 implements copyleft.

- Where to find more resources about CC-BY-SA compliance.

FIXME this list should be more aggressive, but material is not yet present

WARNING: As of November 2014 this part is brand new, and badly needs review, referencing, expansion, error correction, and more.

Freedom as in Free Culture, Documentation, Education…

Critiques of copyright’s role in concentrating power over and making culture inaccessible have existed throughout the history of copyright. Few contemporary arguments about “copyright in the digital age” have not already been made in the 1800s or before. Though one can find the occasional ad hoc “anti-copyright”, “no rights reserved”, or pro-sharing statement accompanying a publication, use of formalized public licenses for non-software works seems to have begun only after the birth of the free software movement and of widespread internet access among elite populations.

Although they have much older antecedents, contemporary movements to create, share, and develop policy encouraging “cultural commons”, “open educational resources”, “open access scientific publication” and more, have all come of age in the last 10-15 years – after the huge impact of free software was unmistakable. Additionally, these movements have tended to emphasize access, with permissions corresponding to the four freedoms of free software and the use of fully free public licenses as good but optional.

It’s hard not to observe that it seems the free software movement arose more or less shortly after as it became desirable (due to changes in the computing industry and software becoming unambiguously subject to copyright in the United States by 1983), but non-software movements for free-as-in-freedom knowledge only arose after they became more or less inevitable, and only begrudgingly at that. Had a free culture “constructed commons” movement been successful prior to the birth of free software, the benefits to computing would have been great – consider the burdens of privileged access to proprietary culture for proprietary software through DRM and other mechanisms, toll access to computer science literature, and development of legal mechanisms and policy through pioneering trial-and-error.

Alas, counterfactual optimism does not change the present – but might embolden our visions of what freedom can be obtained and defended going forward. Copyleft policy will surely continue to be an important and controversial factor, so it’s worth exploring the current version of the most popular copyleft license intended for use with non-software works, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC-BY-SA-4.0), the focus of this tutorial.

Free Definitions

When used to filter licenses, the Free Software Definition and Open Source Definition have nearly identical results. For licenses primarily intended for non-software works, the Definition of Free Cultural Works and Open Definition similarly have identical results, both with each other and with the software definitions which they imitate. All copyleft licenses for non-software works must be “free” and “open” per these definitions.

There are various other definitions of “open access”, “open content”, and “open educational resources” which are more subject to interpretation or do not firmly require the equivalent of all four freedoms of the free software definition. While these definitions are not pertinent to circumscribing the concept of copyleft – which is about enforcing all four freedoms, for everyone. But copyleft licenses for non-software works are usually considered “open” per these other definitions, if they are considered at all.

The open access to scientific literature movement, for example, seems to have settled into advocacy for non-copyleft free licenses (CC-BY) on one hand, and acceptance of highly restrictive licenses or access without other permissions on the other. This creates practical problems: for example, nearly all scientific literature either may not be incorporated into Wikipedia (which uses CC-BY-SA) or may not incorporate material developed on Wikipedia – both of which do happen, when the licenses allow it. This tutorial is not the place to propose solutions, but let this problem be a motivator for encouraging more widespread understanding of copyleft policy.

Non-software Copylefts

Copyleft is a compelling concept, so unsurprisingly there have been many attempts to apply it to non-software works – starting with use of GPLv2 for documentation, then occasionally for other texts, and art in various media. Although the GPL was and is perfectly usable for any work subject to copyright, several factors were probably important in preventing it from being the dominant copyleft outside of software:

- the GPL is clearly intended first as a software license, thus requiring some perspective to think of applying to non-software works;

- the FSF’s concern is software, and the organization has not strongly advocated for using the GPL for non-software works;

- further due to the (now previous) importance of its hardcopy publishing business and desire to retain the ability to take legal action against people who might modify its statements of opinion, FSF even developed a non-GPL copyleft license specifically for documentation, the Free Documentation License (FDL; which ceases to be free and thus is not a copyleft if its “invariant sections” and similar features are used);

- a large cultural gap and lack of population overlap between free software and other movements has limited knowledge transfer and abetted reinvention and relearning;

- the question of what constitutes source (“preferred form of the work for making modifications”) for many non-software works.

As a result, several copyleft licenses for non-software works were developed, even prior to the existence of Creative Commons. These include the aforementioned FDL (1998), Design Science License (1999), Open Publication License (1999; like the FDL it has non-free options), Free Art License (2000), Open Game License (2000; non-free options), EFF Open Audio License (2001), LinuxTag Green OpenMusic License (2001; non-free options) and the QING Public License (2002). Additionally several copyleft licenses intended for hardware designs were proposed starting in the late 1990s if not sooner (the GPL was then and is now also commonly used for hardware designs, as is now CC-BY-SA).

At the end of 2002 Creative Commons launched with 11 1.0 licenses and a public domain dedication. The 11 licenses consisted of every non-mutually exclusive combination of at least one of the Attribution (BY), NoDerivatives (ND), NonCommercial (NC), and ShareAlike (SA) conditions (ND and SA are mutually exclusive; NC and ND are non-free). Three of those licenses were free (as was the public domain dedication), two of them copyleft: CC-SA-1.0 and CC-BY-SA-1.0.

Creative Commons licenses with the BY condition were more popular, so the 5 without (including CC-SA) were not included in version 2.0 of the licenses. Although CC-SA had some advocates, all who felt very strongly in favor of free-as-in-freedom, its incompatibility with CC-BY-SA (meaning had CC-SA been widely used, the copyleft pool of works would have been further fragmented) and general feeling that Creative Commons had created too many licenses led copyleft advocates who hoped to leverage Creative Commons to focus on CC-BY-SA.

Creative Commons began with a small amount of funding and notoriety, but its predecessors had almost none (FSF and EFF had both, but their entries were not major focuses of those organizations), so Creative Commons licenses (copyleft and non-copyleft, free and non-free) quickly came to dominate the non-software public licensing space. The author of the Open Publication License came to recommend using Creative Commons licenses, and the EFF declared version 2.0 of the Open Audio License compatible with CC-BY-SA and suggested using the latter. Still, at least one copyleft license for “creative” works was released after Creative Commons launched: the Against DRM License (2006), though it did not achieve wide adoption. Finally a font-specific copyleft license (SIL Open Font License) was introduced in 2005 (again the GPL, with a “font exception”, was and is now also used for fonts).

Although CC-BY-SA was used for licensing “databases” almost from its launch, and still is, copyleft licenses specifically intended to be used for databases were proposed starting from the mid-2000s. The most prominent of those is the Open Database License (ODbL; 2009). As we can see public software licenses following the subjection of software to copyright, interest in public licenses for databases followed the EU database directive mandating “sui generis database rights”, which began to be implemented in member state law starting from 1998. How CC-BY-SA versions address databases is covered below.

Aside on share-alike non-free therefore non-copylefts

Many licenses intended for use with non-software works include the “share-alike” aspect of copyleft: if adaptations are distributed, to comply with the license they must be offered under the same terms. But some (excluding those discussed above) do not grant users the equivalent of all four software freedoms. Such licenses aren’t true copylefts, as they retain a prominent exclusive property right aspect for purposes other than enforcing all four freedoms for everyone. What these licenses create are “semicommons” or mixed private property/commons regimes, as opposed to the commons created by all free licenses, and protected by copyleft licenses. One reason non-free public licenses might be common outside software, but rare for software, is that software more obviously requires ongoing maintenance. Without control concentrated through copyright assignment or highly asymmetric contributor license agreements, multi-contributor maintenance quickly creates an “anticommons” – e.g., nobody has adequate rights to use commercially.

These non-free share-alike licenses often aggravate freedom and copyleft advocates as the licenses sound attractive, but typically are confusing, probably do not help and perhaps stymie the cause of freedom. There is an argument that non-free licenses offer conservative artists, publishers, and others the opportunity to take baby steps, and perhaps support better policy when they realize total control is not optimal, or to eventually migrate to free licenses. Unfortunately no rigorous analysis of any of these conjectures exists. The best that can be done might be to promote education about and effective use of free copyleft licenses (as this tutorial aims to do) such that conjectures about the impact of non-free licenses become about as interesting as the precise terms of proprietary software EULAs – demand freedom instead.

In any case, some of these non-free share-alike licenses (also watch out for aforementioned copyleft licenses with non-free and thus non-copyleft options) include: Open Content License (1998), Free Music Public License (2001), LinuxTag Yellow, Red, and Rainbow OpenMusic Licenses (2001), Open Source Music License (2002), Creative Commons NonCommercial-ShareAlike and Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Licenses (2002), Common Good Public License (2003), and Peer Production License (2013). CC-BY-NC-SA is by far the most widespread of these, and has been versioned with the other Creative Commons licenses, through the current version 4.0 (2013).

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike

The remainder of this tutorial exclusively concerns the most widespread copyleft license intended for non-software works, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike(CC-BY-SA). But, there are actually many CC-BY-SA licenses – 5 versions (6 if you count version 2.1, a bugfix for a few jurisdiction “porting” mistakes), ports to 60 jurisdictions – 96 distinct CC-BY-SA licenses in total. After describing CC-BY-SA and how it differs from the GPL at a high level, we’ll have an overview of the various CC-BY-SA licenses, then a section-by-section walkthrough of the most current and most clear of them – CC-BY-SA-4.0.

CC-BY-SA allows anyone to share and adapt licensed material, for any purpose, subject to providing credit and releasing adaptations under the same terms. The preceding sentence is a severe abridgement of the “human readable” license summary or “deed” provided by Creative Commons at the canonical URL for one of the CC-BY-SA licenses – the actual license or “legalcode” is a click away. But this abridgement, and the longer the summary provided by Creative Commons are accurate in that they convey CC-BY-SA is a free, copyleft license.

GPL and CC-BY-SA differences

FIXME this section ought refernence GPL portion of tutorial extensively

There are several differences between the GPL and CC-BY-SA that are particularly pertinent to their analysis as copyleft licenses.

The most obvious such difference is that CC-BY-SA does not require offering works in source form, that is their preferred form for making modifications. Thus CC-BY-SA makes a huge tradeoff relative to the GPL – CC-BY-SA dispenses with a whole class of compliance questions which are more ambiguous for some creative works than they are for most software – but in so doing it can be seen as a much weaker copyleft.

Copyleft is sometimes described as a “hack” or “judo move” on copyright, but the GPL makes two moves, though it can be hard to notice they are conceptually different moves, without the contrast provided by a license like CC-BY-SA, which only substantially makes one move. The first move is to neutralize copyright restrictions – adaptations, like the originally licensed work, will effectively not be private property (of course they are subject to copyright, but nobody can exercise that copyright to prevent others’ use). If copyright is a privatized regulatory system (it is), the first move is deregulatory. The second move is regulatory – the GPL requires offer of source form, a requirement that would not hold if copyright disappeared, absent a different regulatory regime which mandated source revelation (one can imagine such a regime on either “pragmatic” grounds, e.g., in the interest of consumer protection, or on the grounds of enforcing software freedom as a universal human right).

FIXME analysis of differences in copyleft scope (eg interplay of derivative works, modified copies, collections, aggregations, containers) would be good here but might be difficult to avoid novel research

CC-BY-SA makes the first move but adds the second in a limited fashion. It does not require offer of preferred form for modification nor any variation thereof (e.g., the FDL requires access to a “transparent copy”). CC-BY-SA does prohibit distribution with “effective technical measures” (i.e., digital restrictions management or DRM) if doing so limits the freedoms granted by the license. We can see that this is regulatory because absent copyright and any regime specifically limiting DRM, such distribution would be perfectly legal. Note the GPL does not prohibit distribution with DRM, although its source requirement makes DRM superfluous, and somewhat analogously, of course GPLv3 carefully regulates distribution of GPL’d software with locked-down devices – to put it simply, it requires keys rather than prohibiting locks. Occasionally a freedom advocate will question whether CC-BY-SA’s DRM prohibition makes CC-BY-SA a non-free license. Few if any questioners come down on the side of CC-BY-SA being non-free, perhaps for two reasons: first, overwhelming dislike of DRM, thus granting the possibility that CC-BY-SA’s approach could be appropriate for a license largely used for cultural works; second, the DRM prohibition in CC-BY-SA (and all CC licenses) seems to be mainly expressive – there are no known enforcements, despite the ubiquity of DRM in games, apps, and media which utilize assets under various CC licenses.

Another obvious difference between the GPL and CC-BY-SA is that the former is primarily intended to be used for software, and the latter for cultural works (and, with version 4.0, databases). Although those are the overwhelming majority of uses of each license, there are areas in which both are used, e.g., for hardware design and interactive cultural works, where there is not a dominant copyleft practice or the line between software and non-software is not absolutely clear.

This brings us to the third obvious difference, and provides a reason to mitigate it: the GPL and CC-BY-SA are not compatible, and have slightly different compatibility mechanisms. One cannot mix GPL and CC-BY-SA works in a way that creates a derivative work and comply with either of them. This could change – CC-BY-SA-4.0 introduced the possibility of Creative Commons declaring CC-BY-SA-4.0 one-way (as a donor) compatible with another copyleft license – the GPL is obvious candidate for such compatibility. Discussion is expected to begin in late 2014, with a decision sometime in 2015. If this one-way compatibility were to be enacted, one could create an adaptation of a CC-BY-SA work and release the adaptation under the GPL, but not vice-versa – which makes sense given that the GPL is the stronger copyleft.

The GPL has no externally declared compatibility with other licenses mechanism (and note no action from the FSF would be required for CC-BY-SA-4.0 to be made one-way compatible with the GPL). The GPL’s compatibility mechanism for later versions of itself differs from CC-BY-SA’s in two ways: the GPL’s is optional, and allows for use of the licensed work and adaptations under later versions; CC-BY-SA’s is non-optional, but only allows for adaptations under later versions.

Fourth, using slightly different language, the GPL and CC-BY-SA’s coverage of copyright and similar restrictions should be identical for all intents and purposes (GPL explicitly notes “semiconductor mask rights” and CC-BY-SA-4.0 “database rights” but neither excludes any copyright-like restrictions). But on patents, the licenses are rather different. CC-BY-SA-4.0 explicitly does not grant any patent license, while previous versions were silent. GPLv3 has an explicit patent license, while GPLv2’s patent license is implied (see [gpl-implied-patent-grant] and [GPLv3-drm] for details). This difference ought give serious pause to anyone considering use of CC-BY-SA for works potentially subject to patents, especially any potential licensee if CC-BY-SA licensor holds such patents. Fortunately Creative Commons has always strongly advised against using any of its licenses for software, and that advice is usually heeded; but in the space of hardware designs Creative Commons has been silent, and unfortunately from a copyleft (i.e., use mechanisms at disposal to enforce user freedom) perspective, CC-BY-SA is commonly used (all the more reason to enable one-way compatibility, allowing such projects to migrate to the stronger copyleft).

The final obvious difference pertinent to copyleft policy between the GPL and CC-BY-SA is purpose. The GPL’s preamble makes it clear its goal is to guarantee software freedom for all users, and even without the preamble, it is clear that this is the Free Software Foundation’s driving goal. CC-BY-SA (and other CC licenses) state no purpose, and (depending on version) are preceded with a disclaimer and neutral “considerations for” licensors and licensees to think about (the CC0 public domain dedication is somewhat of an exception; it does have a statement of purpose, but even that has more of a feel of expressing yes-I-really-mean-to-do-this than a social mission). Creative Commons has always included elements of merely offering copyright holders additional choices and of purposefully creating a commons. While CC-BY-SA (and initially CC-SA) were just among the 11 non-mutually exclusive combinations of “BY”, “NC”, “ND”, and “SA”, freedom advocates quickly adopted CC-BY-SA as “the” copyleft for non-software works (surpassing previously existing non-software copylefts mentioned above). Creative Commons has at times recognized the special role of CC-BY-SA among its licenses, e.g., in a statement of intent regarding the license made in order to assure Wikimedians considering changing their default license from the FDL to CC-BY-SA that the latter, including its steward, was acceptably aligned with the Wikimedia movement (itself probably more directly aligned with software freedom than any other major non-software commons).

FIXME possibly explain why purpose might be relevant, eg copyleft instrument as totemic expression, norm-setting, idea-spreading

FIXME possibly mention that CC-BY-SA license text is free (CC0)

There are numerous other differences between the GPL and CC-BY-SA that are not particularly interesting for copyleft policy, such as the exact form of attribution and notice, and how license translations are handled. Many of these have changed over the course of CC-BY-SA versioning.

CC-BY-SA versions

FIXME section ought explain jurisdiction ports

This section gives a brief overview of changes across the main versions (1.0, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, and 4.0) of CC-BY-SA, again focused on changes pertinent to copyleft policy. Creative Commons maintains a page detailing all significant changes across versions of all of its CC-BY* licenses, in many cases linking to detailed discussion of individual changes.

As of late 2014, versions 2.0 (the one called “Generic”; there are also 18 jurisdiction ports) and 3.0 (called “Unported”; there are also 39 ports) are by far the most widely used. 2.0 solely because it is the only version that the proprietary web image publishing service Flickr has ever supported. It hosts 27 million CC-BY-SA-2.0 photos and remains the go-to general source for free images (though it may eventually be supplanted by Wikimedia Commons, some new proprietary service, or a federation of free image sharing sites, perhaps powered by GNU MediaGlobin). 3.0 both because it was the current version far longer (2007-2013) than any other and because it has been adopted as the default license for most Wikimedia projects.

However apart from the brief notes on each version, we will focus on 4.0 for a section-by-section walkthrough in the next section, as 4.0 is improved in several ways, including understandability, and should eventually become the most widespread version, both because 4.0 is intended to remain the current version for the indefinite and long future, and it would be reasonable to predict that Wikimedia projects will make CC-BY-SA-4.0 their default license in 2015 or 2016.

FIXME subsections might not be the right strcuture or formatting here

1.0 (2002-12-16)

CC-BY-SA-1.0 set the expectation for future versions. But the most notable copyleft policy feature (apart from the high level differences with GPLv2, such as not requiring source) was no measure for compatibility with future versions (nor with the CC-SA-1.0, also a copyleft license, nor with pre-existing copyleft licenses such as GPL, FDL, FAL, and others, nor with CC jurisdiction ports, of which there were 3 for 1.0).

2.0 (2004-05-25)

CC-BY-SA-2.0 made itself compatible with future versions and CC jurisdiction ports of the same version. Creative Commons did not version CC-SA, leaving CC-BY-SA-2.0 as “the” CC copyleft license. CC-BY-SA-2.0 also adds the only clarification of what constitutes a derivative work, making “synchronization of the Work in timed-relation with a moving image” subject to copyleft.

2.5 (2005-06-09)

CC-BY-SA-2.5 makes only one change, to allow licensor to designate another party to receive attribution. This does not seem interesting for copyleft policy, but the context of the change is: it was promoted by the desire to make attribution of mass collaborations easy (and on the other end of the spectrum, to make it possible to clearly require giving attribution to a publisher, e.g., of a journal). There was a brief experiment in branding CC-BY-SA-2.5 as the “CC-wiki” license. This was an early step toward Wikimedia adopting CC-BY-SA-3.0, four years later.

3.0 (2007-02-23)

CC-BY-SA-3.0 introduced a mechanism for externally declaring bilateral compatibility with other licenses. This mechanism to date has not been used for CC-BY-SA-3.0, in part because another way was found for Wikimedia projects to change their default license from FDL to CC-BY-SA: the Free Software Foundation released FDL 1.3, which gave a time-bound permission for mass collaboration sites to migrate to CC-BY-SA. While not particularly pertinent to copyleft policy, it’s worth noting for anyone wishing to study old versions in depth that 3.0 is the first version to substantially alter the text of most of the license, motivated largely by making the text use less U.S.-centric legal language. The 3.0 text is also considerably longer than previous versions.

4.0 (2013-11-25)

CC-BY-SA-4.0 added to 3.0’s external compatibility declaration mechanism by allowing one-way compatibility. After release of CC-BY-SA-4.0 bilateral compatibility was reached with FAL-1.3. As previously mentioned, one-way compatibility with GPLv3 will soon be discussed.

4.0 also made a subtle change in that an adaptation may be considered to be licensed solely under the adapter’s license (currently CC-BY-SA-4.0 or FAL-1.3, in the future potentially GPLv3 or or a hypothetical CC-BY-SA-5.0). In previous versions licenses were deemed to “stack” – if a work under CC-BY-SA-2.0 were adapted and released under CC-BY-SA-3.0, users of the adaptation would need to comply with both licenses. In practice this is an academic distinction, as compliance with any compatible license would tend to mean compliance with the original license. But for a licensee using a large number of works that wished to be extremely rigorous, this would be a large burden, for it would mean understanding every license (including those of jurisdiction ports not in English) in detail.

The new version is also an even more complete rewrite of 3.0 than 3.0 was of previous versions, completing the “internationalization” of the license, and actually decreasing in length and increasing in readability.

Additionally, 4.0 consistently treats database (licensing them like other copyright-like rights) and moral rights (waiving them to the extent necessary to exercise granted freedoms) – in previous versions some jurisdiction ports treated these differently – and tentatively eliminates the need for jurisdiction ports. Official linguistic translations are underway (Finnish is the first completed) and no legal ports are planned for.

4.0 is the first version to explicitly exclude a patent (and less problematically, trademark) license. It also adds two features akin to those found in GPLv3: waiver of any right licensor may have to enforce anti-circumvention if DRM is applied to the work, and reinstatement of rights after termination if non-compliance corrected within 30 days.

Finally, 4.0 streamlines the attribution requirement, possibly of some advantage to massive long-term collaborations which historically have found copyleft licenses a good fit.

The 4.0 versioning process was much more extensively researched, public, and documented than previous CC-BY-SA versionings; see https://wiki.creativecommons.org/4.0 for the record and https://wiki.creativecommons.org/Version_4 for a summary of final decisions.

CC-BY-SA-4.0 International section-by-section

FIXME arguably this section ought be the substance of the tutorial, but is very thin and weak now

FIXME formatted/section-referenced copy of license should be added to license-texts.tex and referenced throughout

The best course of action at this juncture would be to read http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode – the entire text is fairly easy to read, and should be quickly understood if one has the benefit of study of other public licenses and of copyleft policy.

The following walk-through will simply call out portions of each section one may wish to study especially closely due to their pertinence to copyleft policy issues mentioned above.

FIXME subsections might not be the right structure or formatting here

1 – Definitions

The first three definitions – “Adapted Material”, “Adapter’s License”, and “BY-SA Compatible License” are crucial to understanding copyleft scope and compatibility.

2 – Scope

The license grant is what makes all four freedoms available to licensees. This section is also where waiver of DRM anti-circumvention is to be found, also patent and trademark exclusions.

3 – License Conditions

This section contains the details of the attribution and share-alike requirements; the latter read closely with aforementioned definitions describe the copyleft aspect of CC-BY-SA-4.0.

4 – Sui Generis Database Rights

This section describes how the previous grant and condition sections apply in the case of a database subject to sui generis database rights. This is an opportunity to go down a rabbit-hole of trying to understand sui generis database rights. Generally, this is a pointless exercise. You can comply with the license in the same way you would if the work were subject only to copyright – and determining whether a database is subject to copyright and/or sui generis database rights is another pit of futility. You can license databases under CC-BY-SA-4.0 and use databases subject to the same license as if they were any other sort of work.

5 – Disclaimer of Warranties and Limitation of Liability

Unsurprisingly, this section does its best to serve as an “absolute disclaimer and waiver of all liability.”

6 – Term and Termination

This section is similar to GPLv3, but without special provision for cases in which the licensor wishes to terminate even cured violations.

7 – Other Terms and Conditions

Though it uses different language, like the GPL, CC-BY-SA-4.0 does not allow additional restrictions not contained in the license. Unlike the GPL, CC-BY-SA-4.0 does not have an explicit additional permissions framework, although effectively a licensor can offer any other terms if they are the sole copyright holder (the license is non-exclusive), including the sorts of permissions that would be structured as additional permissions with the GPL. Creative Commons has sometimes called offering of separate terms (whether additional permissions or “proprietary relicensing”) the confusing name “CC+”; however where this is encountered at all it is usually in conjunction with one of the non-free CC licenses. Perhaps CC-BY-SA is not a strong enough copyleft to sometimes require additional permissions, or be used to gain commercially valuable asymmetric rights, in contrast with the GPL.

8 – Interpretation

Nothing surprising here. Note that CC-BY-SA does not “reduce, limit, restrict, or impose conditions on any use of the Licensed Material that could lawfully be made without permission under this Public License.” This is a point that Creative Commons has always been eager to make about all of its licenses. GPLv3 also “acknowledges your rights of fair use or other equivalent”. This may be a wise strategy, but should not be viewed as mandatory for any copyleft license – indeed, the ODbL attempts (somewhat self-contradictorily; it also acknowledges fair use or other rights to use) make its conditions apply even for works potentially subject to neither copyright nor sui generis database rights.

Enforcement

There are only a small number of court cases involving any Creative Commons license. Creative Commons lists these and some related cases at https://wiki.creativecommons.org/Case_Law.

Only two of those cases concern enforcing the terms of a CC-BY-SA license (Gerlach v. DVU in Germany, and No. 71036 N. v. Newspaper in a private Rabbinical tribunal) each hinged on attribution, not share-alike.

Further research could uncover out of compliance uses being brought into compliance without lawsuit, however no such research, nor any hub for conducting such compliance work, is known. Editors of Wikimedia Commons document some external uses of Commons-hosted media, including whether user are compliant with the relevant license for the media (often CC-BY-SA), resulting in a category listing non-compliant uses (which seem to almost exclusively concern attribution).

Compliance Resources

FIXME this section is just a stub; ideally there would also be an additional section or chapter on CC-BY-SA compliance

Creative Commons has a page on ShareAlike interpretation as well as an extensive Frequently Asked Questions for licensees which addresses compliance with the attribution condition.

English Wikipedia’s and Wikimedia Commons’ pages on using material outside of Wikimedia projects provide valuable information, as the majority of material on those sites is CC-BY-SA licensed, and their practices are high-profile.

FIXME there is no section on business use of CC-BY-SA; there probably ought to be as there is one for GPL, though there’d be much less to put.

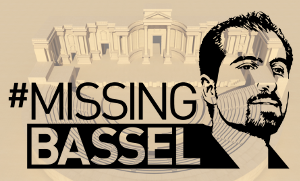

Today is Bassel Khartabil’s 35th birthday and his 1530th day of detention in Syria, and the 233rd day since he was moved to an unknown location, and not heard from since (previously: 1, 2, 3). Shortly after his disappearance last year I helped organize (CFP) a book sprint in his honor and calling for his freedom.

Today is Bassel Khartabil’s 35th birthday and his 1530th day of detention in Syria, and the 233rd day since he was moved to an unknown location, and not heard from since (previously: 1, 2, 3). Shortly after his disappearance last year I helped organize (CFP) a book sprint in his honor and calling for his freedom.