Day 2 of the Collaborative Futures book sprint saw the writing of a number of chapters and the creation of a much more fleshed out table of contents. I spent too much time interrupted by other work and threading together a chapter (feels more like a long blog post) on “Other People’s Computers” from old sources and the theme of supporting collaboration. The current draft is pasted below because that’s easier than extracting links to sources.

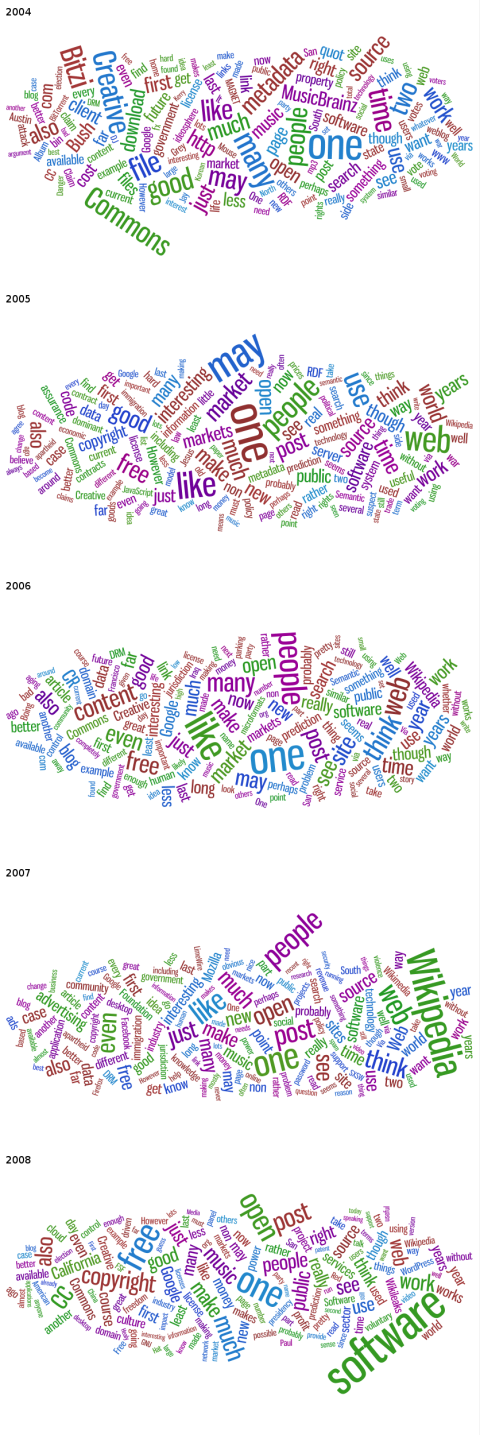

Another tangential observation about the group: I noted a fair amount of hostility toward Wikipedia, the Wikimedia Foundation, and Mediawiki on the notion that they have effectively sucked the air out of other potential projects and models of collaboration, even other wiki software. Of course I am a huge fan of Wikipedia — I think its centralization has allowed it to scale in a way not possible otherwise — it has made the community-centric collaboration pie bigger — and we are very fortunate that such a dominant service has gotten so much right, at least from a freedom perspective. However, the underlying criticism is not without merit, and I tried to incorporate a productive and very brief version of it into the draft.

Also see Mushon Zer-Aviv’s entertaining post on day 2.

Other People’s Computers

Partly because they’re location-transparent and web-integrated, browser apps support social interaction more easily than desktop apps.

Kragen Sitaker, “What’s wrong with HTTP”, http://lists.canonical.org/pipermail/kragen-tol/2006-November/000841.html

Much of what we call collaboration occurs on web sites (more generally, software services), particularly collaboration among many distributed users. Direct support for collaboration, and more broadly for social features, is simply easier in a centralized context. It is possible to imagine a decentralized Wikipedia or Facebook, but building such services with sufficient ease of use, features, and robustness to challenge centralized web sites is a very difficult challenge.

Why does this matter? The web is great for collaboration, let’s celebrate that! However, making it relatively easy for people to work together in the specific way offered by a web site owner is a rather impoverished vision of what the web (or more generally, digital networks) could enable, just as merely allowing people to run programs on their computers in the way program authors intended is an impoverished vision of personal computing.

Free software allows users control their own computing and to help other users by retaining the ability to run, modify, and share software for any purpose. Whether the value of this autonomy is primarily ethical, as often framed by advocates of the term free software, or primarily practical, as often framed by advocates of the term open source, any threat to these freedoms has to be of deep concern to anyone interested in the future of collaboration, both in terms what collaborations are possible and what interests control and benefit from those collaborations.

Web sites and special-purpose hardware […] do not give me the same freedoms general-purpose computers do. If the trend were to continue to the extent the pundits project, more and more of what I do today with my computer will be done by special-purpose things and remote servers.

What does freedom of software mean in such an environment? Surely it’s not wrong to run a Web site without offering my software and databases for download. (Even if it were, it might not be feasible for most people to download them. IBM’s patent server has a many-terabyte database behind it.)

I believe that software — open-source software, in particular — has the potential to give individuals significantly more control over their own lives, because it consists of ideas, not people, places, or things. The trend toward special-purpose devices and remote servers could reverse that.

Kragen Sitaker, “people, places, things, and ideas “, http://lists.canonical.org/pipermail/kragen-tol/1999-January/000322.html

What are the prospects and strategies for keeping the benefits of free software in an age of collaboration mediated by software services? One strategy, argued for in “The equivalent of free software for online services” by Kragen Sitaker (see http://lists.canonical.org/pipermail/kragen-tol/2006-July/000818.html), is that centralized services need to be re-implemented as peer-to-peer services that can be run as free software on computers under users’ control. This is an extremely interesting strategy, but a very long term one, for it is hard, being at least both a computer science and a social challenge.

Abstinence from software services may be a naive and losing strategy in both the short and long term. Instead, we can both work on decentralization as well as attempt to build services that respect user’s autonomy:

Going places I don’t individually control — restaurants, museums, retail stores, public parks — enriches my life immeasurably. A definition of “freedom†where I couldn’t leave my own house because it was the only space I had absolute control over would not feel very free to me at all. At the same time, I think there are some places I just don’t want to go — my freedom and physical well-being wouldn’t be protected or respected there.

Similarly, I think that using network services makes my computing life fuller and more satisfying. I can do more things and be a more effective person by spring-boarding off the software on other peoples’ computers than just with my own. I may not control your email server, but I enjoy sending you email, and I think it makes both of our lives better.

And I think that just as we can define a level of personal autonomy that we expect in places that belong to other people or groups, we should be able to define a level of autonomy that we can expect when using software on other people’s computers. Can we make working on network services more like visiting a friends’ house than like being locked in a jail?

We’ve made a balance between the absolute don’t-use-other-people’s-computers argument and the maybe-it’s-OK-sometimes argument in the Franklin Street Statement. Time will tell whether we can craft a culture around Free Network Services that is respectful of users’ autonomy, such that we can use other computers with some measure of confidence.

Evan Prodromou, “RMS on Cloud Computing: “Stupidity—, CC BY-SA, http://autonomo.us/2008/09/rms-on-cloud-computing-stupidity/

The Franklin Street Statement on Freedom and Network Services is a beginning group attempt to distill actions users, service providers (the “other people” here), and developers should take to retain the benefits of free software in an era of software services:

The current generation of network services or Software as a Service can provide advantages over traditional, locally installed software in ease of deployment, collaboration, and data aggregation. Many users have begun to rely on such services in preference to software provisioned by themselves or their organizations. This move toward centralization has powerful effects on software freedom and user autonomy.

On March 16, 2008, a workgroup convened at the Free Software Foundation to discuss issues of freedom for users given the rise of network services. We considered a number of issues, among them what impacts these services have on user freedom, and how implementers of network services can help or harm users. We believe this will be an ongoing conversation, potentially spanning many years. Our hope is that free software and open source communities will embrace and adopt these values when thinking about user freedom and network services. We hope to work with organizations including the FSF to provide moral and technical leadership on this issue.

We consider network services that are Free Software and which share Free Data as a good starting-point for ensuring users’ freedom. Although we have not yet formally defined what might constitute a ‘Free Service’, we do have suggestions that developers, service providers, and users should consider:

Developers of network service software are encouraged to:

- Use the GNU Affero GPL, a license designed specifically for network service software, to ensure that users of services have the ability to examine the source or implement their own service.

- Develop freely-licensed alternatives to existing popular but non-Free network services.

- Develop software that can replace centralized services and data storage with distributed software and data deployment, giving control back to users.

Service providers are encouraged to:

- Choose Free Software for their service.

- Release customizations to their software under a Free Software license.

- Make data and works of authorship available to their service’s users under legal terms and in formats that enable the users to move and use their data outside of the service. This means:

- Users should control their private data.

- Data available to all users of the service should be available under terms approved for Free Cultural Works or Open Knowledge.

Users are encouraged to:

- Consider carefully whether to use software on someone else’s computer at all. Where it is possible, they should use Free Software equivalents that run on their own computer. Services may have substantial benefits, but they represent a loss of control for users and introduce several problems of freedom.

- When deciding whether to use a network service, look for services that follow the guidelines listed above, so that, when necessary, they still have the freedom to modify or replicate the service without losing their own data.

Franklin Street Statement on Freedom and Network Services, CC BY-SA, http://autonomo.us/2008/07/franklin-street-statement/

As challenging as the Franklin Street Statement appears, additional issues must be addressed for maximum autonomy, including portable identifiers:

A Free Software Definition for the next decade should focus on the user’s overall autonomy- their ability not just to use and modify a particular piece of software, but their ability to bring their data and identity with them to new, modified software.

Such a definition would need to contain something like the following minimal principles:

- data should be available to the users who created it without legal restrictions or technological difficulty.

- any data tied to a particular user should be available to that user without technological difficulty, and available for redistribution under legal terms no more restrictive than the original terms.

- source code which can meaningfully manipulate the data provided under 1 and 2 should be freely available.

- if the service provider intends to cease providing data in a manner compliant with the first three terms, they should notify the user of this intent and provide a mechanism for users to obtain the data.

- a user’s identity should be transparent; that is, where the software exposes a user’s identity to other users, the software should allow forwarding to new or replacement identities hosted by other software.

Luis Villia, “Voting With Your Feet and Other Freedoms”, CC BY-SA, http://tieguy.org/blog/2007/12/06/voting-with-your-feet-and-other-freedoms/

Fortunately the oldest and at least until recently most ubiqitous network service — email — accomodates portable identifiers. (Not to mention that email is the lowest common denominator for much collaboration — sending attachments back and forth.) Users of a centralized email service like Gmail can retain a great deal of autonomy if they use an email address at a domain they control and merely route delivery to the service — though of course most users use the centralized provier’s domain.

It is worth noting that the more recent and widely used if not ubiquitous instant messaging protocol XMPP as well as the brand new and little used Wave protocol are architected similar to email, though use of non-provider domains seems even less common, and in the case of Wave, Google is currently the only service provider.

It may be valuable to assess software services from the respect of community autonomy as well as user autonomy. The former may explicitly note requirements for the product of collaboration — non-private data, roughly — as well as service governance:

In cases were one accepts a centralized web application, should one demand that application be somehow constitutionally open? Some possible criteria:

- All source code for the running service should be published under an open source license and developer source control available for public viewing.

- All private data available for on-demand export in standard formats.

- All collaboratively created data available under an open license (e.g., one from Creative Commons), again in standard formats.

- In some cases, I am not sure how rare, the final mission of the organization running the service should be to provide the service rather than to make a financial profit, i.e., beholden to users and volunteers, not investors and employees. Maybe. Would I be less sanguine about the long term prospects of Wikipedia if it were for-profit? I don’t know of evidence for or against this feeling.

Mike Linksvayer, “Constitutionally open services”, CC0, https://gondwanaland.com/mlog/2006/07/06/constitutionally-open-services/

Software services are rapidly developing and subject to much hype — referred to by buzzwords such as cloud computing. However, some of the most potent means of encouraing autonomy may be relatively boring — for example, making it easier to maintain one’s own computer and deploy slightly customized software in a secure and foolproof fashion. Any such development helps traditional users of free software as well as makes doing computing on one’s own computer (which may be a “personal server” or virtual machine that one controls) more attractive.

Perhaps one of the most hopeful trends is relatively widespead deployment by end users of free software web applications like WordPress and MediaWiki. StatusNet, free software for microblogging, is attempting to replicate this adoption success, but also includes technical support for a form of decentralization (remote subscription) and a legal requirement for service providers to release modifications as free software via the AGPL.

This section barely scratches the surface of the technical and social issues raised by the convergence of so much of our computing, in particular computing that facilitates collaboration, to servers controlled by “other people”, in particular a few large service providers. The challenges of creating autonomy-respecting alternatives should not be understated.

One of those challenges is only indirectly technical: decentralization can make community formation more difficult. To the extent the collaboration we are interested in requires community, this is a challenge. However, easily formed but inauthentic and controlled community also will not produce the kind of collaboration we are interested in.

We should not limit our imagination to the collaboration faciliated by the likes of Facebook, Flickr, Google Docs, Twitter, or other “Web 2.0” services. These are impressive, but then so was AOL two decades ago. We should not accept a future of collaboration mediated by centralized giants now, any more than we should have been, with hindsight, happy to accept information services dominated by AOL and its near peers.

Wikipedia is both held up as an exemplar of collaboration and is a free-as-in-freedom service: both the code and the content of the service are accessible under free terms. It is also a huge example of community governance in many respects. And it is undeniably a category-exploding success: vastly bigger and useful in many more ways than any previous encyclopedia. Other software and services enabling autonomous collaboration should set their sites no lower — not to merely replace an old category, but to explode it.

However, Wikipedia (and its MediaWiki software) are not the end of the story. Merely using MediaWiki for a new project, while appropriate in many cases, is not magic pixie dust for enabling collaboration. Affordances for collaboration need to be built into many different types of software and services. Following Wikipedia’s lead in autonomy is a good idea, but many experiments should be encouraged in every other respect. One example could be the young and relatively domain-specific collaboration software that this book is being written with, Booki.

Software services have made “installation” of new software as simple as visiting a web page, social features a click, and provide an easy ladder of adoption for mass collaboration. They also threaten autonomy at the individual and community level. While there are daunting challenges, meeting them means achieving “world domination” for freedom in the most important means of production — computer-mediated collaboration — something the free software movement failed to approach in the era of desktop office software.