Almost always for me ‘patriot’ is a term of derision, but here I mean something specific: putting one’s preferred issues and interests to the side to focus on fixing the relevant institutions, in this case of the state. To make the state stronger (as in less degenerate, not necessarily huger). To make collective action work better. To steer the system away from N-party competitive distribution of public spoils by fixing the system rather than blaming particular groups of outsiders or insiders (i.e., what usually passes as ‘patriotic’).

By that specific meaning, Lawrence Lessig is by far the most patriotic candidate for U.S. temporary dictator. I hope he gets into more polls (and prediction markets) and the debates. In Republic, Lost (2011; pdf; my notes on the book below) Lessig evaluates the chances of a presidential campaign like the one he is running: “Let’s be wildly optimistic: 2 percent.” That sounds fair, but the campaign still makes sense, for building name recognition for a future campaign or for injecting non-atavistic patriotism into the debate (so let him).

The campaign worked on me in the sense that it motivated me to read Republic, Lost (which had been in my virtual ‘fullness of time’ pile). I hadn’t followed Lessig’s anti-corruption efforts closely because I was burned out from working for him at Creative Commons and based on headlines, they looked like a turbocharged version: grand and good basic ideas (roughly fixing knowledge regulation and fixing democracy, respectively), politician-like (now actual politician) total campaigning (both for money and to convince the public; in the short term the free culture movement is surely poorer in both respects relative to a world in which Lessig did not shift focus), and constant startup-like pivoting and gimmicks that seemed to me distractions from the grand and good ideas (but no doubt to him are essential innovations). There are many reasons Creative Commons was not a venue ripe for experimentation, and it seems to (I’m barely involved anymore) have mostly settled into doing something close to commons coordination work I believe it is most suited to, including work on license interoperability and supporting open policy. But in hindsight a venue or series of them (cf. Change Congress, Fix Congress First, Mayday.US, NHRebellion, RootStrikers…) built for experimentation might have made for a more contribution to the [semi]free culture world than did a conservatism-inducing (appropriately) license steward (of which there were already plenty). All of which is to say that I’m looking charitably upon Lessig’s many political experiments, including the various novel aspects of his current campaign, though I can understand how they (the means, not the ends of fixing democracy) could be interpreted as gimmicks.

The campaign worked on me in the sense that it motivated me to read Republic, Lost (which had been in my virtual ‘fullness of time’ pile). I hadn’t followed Lessig’s anti-corruption efforts closely because I was burned out from working for him at Creative Commons and based on headlines, they looked like a turbocharged version: grand and good basic ideas (roughly fixing knowledge regulation and fixing democracy, respectively), politician-like (now actual politician) total campaigning (both for money and to convince the public; in the short term the free culture movement is surely poorer in both respects relative to a world in which Lessig did not shift focus), and constant startup-like pivoting and gimmicks that seemed to me distractions from the grand and good ideas (but no doubt to him are essential innovations). There are many reasons Creative Commons was not a venue ripe for experimentation, and it seems to (I’m barely involved anymore) have mostly settled into doing something close to commons coordination work I believe it is most suited to, including work on license interoperability and supporting open policy. But in hindsight a venue or series of them (cf. Change Congress, Fix Congress First, Mayday.US, NHRebellion, RootStrikers…) built for experimentation might have made for a more contribution to the [semi]free culture world than did a conservatism-inducing (appropriately) license steward (of which there were already plenty). All of which is to say that I’m looking charitably upon Lessig’s many political experiments, including the various novel aspects of his current campaign, though I can understand how they (the means, not the ends of fixing democracy) could be interpreted as gimmicks.

One of my takeaways from Republic, Lost is that the referendum candidacy (Lessig intends to resign after passing one bill, making his candidacy a referendum for that bill) is sort of an anti-gimmick, a credible commitment mechanism, without which any candidate’s calls for changing the system ought be interpreted as hot air. In the book Lessig expresses deep disappointment with Obama, who ran promising fundamental change, which he then failed to deliver or even really attempt, with the consequence of corrupting the non-system-changing reforms he has pushed through (e.g., health care reform contains massive giveaways to drug and insurance industries).

Experimentation with novel commitment mechanisms and anti-gimmicks is great, so I heartily applaud Lessig’s referendum candidacy. But so far it seems to have backfired: the anti-gimmick is interpreted as a gimmick and (not sure if following has been mentioned in press, but is usual response from friends I’ve mentioned the campaign to) the commitment is not taken as credible: it’s still just a politician’s (worthless) promise, power would go to his head, exigencies would intervene, or even if none of this is true, the bill would never pass. On the last bit, Lessig argues that if he won as a referendum candidate, members of Congress would understand the electorate was making an extraordinary demand and pass the bill — they want to be re-elected. Sounds reasonable to me, given the extraordinary circumstance of Lessig being elected without deviation from his referendum platform. The extraordinary circumstance that election would be also seems to me to mitigate the other objections, though less so.

Speaking of power head trips, what about the problem of executive power (thus my preference for calling the U.S. presidency a temporary dictatorship)? Abuse and non-reform thereof has been my biggest disappointment with the Obama administration. I can only recall an indirect mention in Republic, Lost: Congressional deliberation is now rare in part due to members’ need to constantly fundraise, thus, according to a quoted former member, Congress is “failing to live up to its historic role of conducting oversight of the Executive Branch” and “[N]o one today could make a coherent argument that the Congress is the co-equal branch of government the Founders intended it to be.” It does seem totally reasonable that if Congress is non-functional and dependent on concentrated money, the executive branch would also be able to cultivate Congress’ dependency (Lessig does a good job of explaining his use of this term early in the book) and thus thwart Congress as an effective regulator of executive power. I wish Republic, Lost had more on the relationship of Congress and the executive, and related, on Congress and the military/foreign policy/state security complex. To what extent does concentrated money from military contractors, “legislative subsidy” (motivated analysis; a less distracted Congress might make such less needed to the extent it is benign and easier to defend against to the extent it is not) from contractors and the military itself make Congress less able to regulate and indeed eager to go along with disastrous and criminal militarism?

What if politicians could and regularly did make credible commitments to upholding their promises? If the mechanism were not novel and the promises reasonable, perception of gimmickry would largely go away. So would the need for the novelty of a referendum candidacy with a promise of resignation: the referendum would be built in, resignation would be required when a candidate does not uphold their promises, not when they do. Could a stronger commitment be made by a candidate now, without any changes to the law? Would a contract with an intermediary, perhaps a non-profit existing only to enforce candidate promises made to it, be upheld? If politicians upholding their promises is a good thing, shouldn’t a commitment mechanism be built into the law?

Assume for a moment that it would be good for government institutions to make candidate promises enforceable (optionally; a candidate could still make all the hot air promises they wished). We can’t have that reform until the system “rigged” (a term Lessig uses in his campaign, but not appearing in the book) by the need to fundraise from concentrated interests is fixed, because we can’t have any reform until the system is fixed, at least not any reform that isn’t corrupted by having to survive the rigged system. Is it the case that concentrated money in elections is the essential rigging that must be removed before good progress on any other issue can be obtained?

Lessig does make a very good case that dependency of politicians on concentrated money interests is a problem. Three points (among many) stood out to me. First, at the least politicians must spend a huge portion of their time fundraising, making them distracted, relatively ignorant (having to be fundraising rather than studying or discussing issues), and I’d imagine relatively stupid (selection for fundraising tolerance and ability, driving out other qualities). Second, we often go through great lengths to ensure judges are removed from cases in which they have even an appearance of conflict — shouldn’t we want to isolate law makers from even the appearance of corruption just as much, if not more? (Does this not suggest a different reform: bar legislators from any vote in which any impacted party has donated above some very small amount to the legislator’s campaigns?) Third, academic literature on the influence of money in legislative outcomes tends to find little. Lessig argues that this literature is looking for keys under the lamppost because that’s where the light is — it’s easy to look at roll call votes, but almost all of the action is in determining what legislation makes it to a vote.

Intuitively the effect of dependence on concentrated money on agenda setting and thus outcomes ought be large. Is there any literature attempting to characterize how large? I didn’t notice any pointers to such in Rebpublic, Lost, but may have missed them. A comment made late in a forum on Subsidizing Democracy: Can Public Financing Change Politics? indicates that the empirical work hasn’t been done yet, at least not through the lens of the impact on outcomes of various forms of public financing of U.S. state legislature campaigns. But public financing does seem to have big impacts on legislator time dedicated to fundraising, time spent talking to potential voters, and who runs and is elected.

Vying with the brief contrast of demands for independence of judges and legislators for the most valuable portion of Republic, Lost is a brief mention with supporting footnote of U.S. state legislative campaign public funding reforms, particularly in Arizona, Connecticut, and Maine:

Over the past fifteen years, three states have experimented with reforms that come very close to this idea. Arizona, Maine, and Connecticut have all adopted reforms for their own state government that permits members of the legislature (and of some statewide offices) to fund their campaigns through small-dollar contributions only. Though the details of these programs are different, the basic structure of all three is the same: candidates qualify by raising a large number of small contributions; once qualified, the candidates receive funding from the state to run their campaigns.

References about these, include one by Michael G. Miller, author of Subsidizing Democracy (2014). I haven’t read this book, but I did find a recording of a forum on the book held at New America Foundation, which I recommend — the other commentators provide valuable context and critique.

Spencer Overton’s comments, starting at about 30 minutes, seem to give an overview of leading thinking on campaign finance, in particular three points. First money in politics is not the problem, dependency on concentrated money is, therefore subsidizing small contributions in exchange for opting to accept limits on large contributions is a solution (note this reform steers clear of reasonable free speech objections to simply banning concentrated money). Second, mitigating corruption is a good outcome of such a solution, but increasing citizen engagement in politics is another good outcome. I’m fairly certain Lessig would be in strong agreement with these first two points; he mentions Overton’s work on “participation interest” in Republic, Lost. Third, states (and cities, e.g., NYC) are learning from and improving their reforms: the impacts on candidate and legislator behavior studied by Miller (primarily in Arizona, if I understand correctly) are based on reforms which are being improved. Overton in particular mentioned the value of matching small donations on an ongoing basis rather than only using small donations to qualify for a lump subsidy (note this would make the reforms much more similar to Lessig’s proposal).

The mention of U.S. state reforms is in the “strategies” section of Republic, Lost, in a description of the first strategy: simply getting Congress to pass a reform similar to those already passed in a few states. Lessig dismisses this strategy because lobbyists are a concentrated interest standing in its way. I’m not convinced by the dismissal for three reasons. First, aren’t state level reforms an existence proof? Lobbyists exist at the state level and are a potential interest group. Second, just how concentrated is the interest of lobbyists qua lobbyists? They are paid to represent various concentrated interests, but how well do they support the Association of Government Relations Professionals, renamed in 2013 from the American League of Lobbyists? Do lobbyists as a class suffer from all the usual collective action problems? Admittedly, to the extent they do form a coherent interest group, they do know just how to be effective. Third, can’t success at the state and local level drive cultural change (especially if reforms obtain demonstrably improved outcomes, but even if not they change the culture of the farm team for Congress and eventually Congress, by removing selection pressure for tolerance of and skill at fundraising), making passing a bill in Congress even against lobbying interests more feasible? This path does not have the urgency of a national campaign, but by Lessig’s own estimates such urgency is nearly hopeless, e.g., as mentioned above “wildly optimistic: 2 percent” for a presidential campaign.

Regardless of whether he favored a long-term state and local innovation driven strategy, I wish Lessig had written more about state and local reforms in order to make the case that concentrated money is a problem more concrete and less intuitive and that reforms similar to ones he proposes make the sort of essential difference that he claims (changed state outcomes could help demonstrate both things). Perhaps there was not enough experience with state and local reforms that de-concentrated and added money to campaigns to say much about them in Republic, Lost (2011), but is that still the case in the current campaign? I also would have and would appreciate some analysis of the impact of various campaign financing regimes around the world on the campaigns, composition, behavior, and outcomes of legislatures. The sole contemporary non-U.S. legislature mentioned in Republic, Lost is the UK House of Commons, which often deliberates as a body, unlike the U.S. Congress. Is this an outcome of different campaign financing? Lessig doesn’t say. Yes cross-country comparisons are fraught but surely some would be helpful in characterizing the size of the problem of concentrated money and the potential impact of reform.

While I’m on the “strategies” section of Republic, Lost, a few notes on the other three proposed. Recall the first (discussed above) is passing a bill in the U.S. Congress, dubbed “The Conventional Game”. The second is “An Unconventional (Primary) Game” strikes me as classic Lessig — it involves getting celebrities on board (each celebrity would contest primaries for U.S. Congress in multiple districts), and I don’t quite get it. He gives it a “wildly optimistic: 5 percent” chance of working. With that caveat, and a reminder to myself about taking these proposals charitably, it is a creative proposal at the least. I suppose it could be thought of as a way to turn a legislative primary election season into a referendum on a single issue. Crucially for the single issue of campaign finance reform, without the cooperation of incumbents fit for the current system, or as Lessig writes, it would be a strategy of “peaceful terrorism” on such incumbents.

The third strategy is “An Unconventional Presidential Game”, which the current Lessig campaign seems to be following closely.

The fourth strategy is “The Convention Game”:

A platform for pushing states to call for a federal convention would begin by launching as many shadow conventions as is possible. In schools, in universities—wherever such deliberation among citizens could occur. The results of those shadow conventions would be collected, and posted, and made available for critique. And as they demonstrated their own sensibility, they would support the push for states to call upon Congress to remove the shadow from these conventions. Congress would then constitute a federal convention. That convention—if my bet proves correct—would be populated by a random selection of citizens drawn from the voter rolls. That convention would then meet, deliberate, and propose new amendments to the Constitution. Congress would refer those amendments out to the states for their ratification.

In the book, this strategy seems to be where Lessig’s heart is. He gives it “with enough entrepreneurial state representatives” a “10 percent at a minimum” chance of success. A constitutional convention brings up all kinds of arguments; I recommend reading the chapter in Republic, Lost. I include it in this post for completeness, for its reliance on entrepreneurial state representatives (the long-term “conventional game” also does, see above), and most of all for its inclusion of — sortition (random selection)! That is my preferred reform for choosing legislators (and indirectly, executives, including national temporary dictators), removing not only dependence on concentrated money, but dependence on campaigning, which surely also has a strong selection effect, for tolerance of and skill at campaigning, against other qualities. But much like range voting, land value taxation, and prediction markets (and others; let’s see how the new thing, quadratic voting, fares), sortition’s real world use is about the inverse of its theoretical beauty (dependencies at odds with apparent objectives or corruption broadly conceived is probably a big part of the story for each, example; note similarity to my question about broad conceptions of commoning). Oh well. Perhaps de-concentrating money in political campaigns is a first step toward more ideal institutions.

But is it the essential first step claimed by Lessig, before which no other reform can go forward uncorrupted?

In Republic, Lost Lessig does a decent job of turning stereotypical left and right objections into arguments that de-concentrating money in political campaigns is the essential first step. The left objection is that wealth inequality must be addressed first; without doing so the wealthy will always find ways to rig the system in their favor. Turn: you can’t expect to achieve wealth redistribution when the system is rigged by concentrated money from the wealthy. The right objection is that the essential problem is that government is doing too much; reduce the size and scope of government first, then its remaining essential functions (if any) can run like Swiss clockwork. Turn: you can’t expect to reduce the size and scope of government when the system is rigged by concentrated money protecting every grotesque program. I don’t expect these turns will convince many of those strongly convinced that the essential problem is wealth inequality or big government. In small part because it’s not entirely clear, as for lobbyists, that “the wealthy” or “big government” constitute concentrated interests able to use the rigged system to protect themselves from what a dream crisis or candidate of the left or right would do to them. Rather, there are a bunch of different concentrated interests that probably tend to increase upward wealth redistribution and the size of government. Systematic reform would mitigate these tendencies but from the left or right perspective is not ‘striking at the root’ and does not have the feel of urgency of a dream crisis or candidate. If a referendum candidate is an effective vehicle, why not one who promises to hack at the rich or at government, then resign? But for the not entirely committed, perhaps de-concentrating money in political campaigns can be made to seem a good first step, possibly an essential non-revolutionary (that is, not a catastrophic invitation to trolls) strategy.

Another objection to de-concentration of money in political campaigns as the essential first step is lots that ought be construed as reform is not dependent on elected legislatures. Much does not go directly through government. Everything from organizations to culture to interpersonal relationships all have scope for independent reform, which happens all the time. As do other organs of government such as courts and administration. These objections could be turned to apologia for the primacy of de-concentration of money in political campaigns. They explain why one can perceive good reform happening (e.g., marriage equality) when Lessig tells us no good reform is possible until campaign finance is reformed. These independent sources of reform mask just what a poor job the U.S. Congress does. Clearly lots of important reform is dependent on action by the U.S. Congress, and any such reform is wholly blocked or corrupted by having to survive a U.S. Congress dependent on concentrated money, which meanwhile also passes all kinds of anti-reform.

There are numerous reforms which would reduce corruption, capture, and inappropriate dependency which could be taken as objections to campaign finance reform as the essential first reform, or buttress the argument for it, depending on their dependence on a U.S. Congress dependent on fundraising from concentrated money. The Scourge of Upward Redistribution, a recent article by Steven Teles, surveys a number of such reforms, which tend to give regulatory decision makers more resources and push regulatory decisions into more accessible venues, making decisions less dependent on and controlled by concentrated interests. The control is not just about venue, but imagination: broader participation in regulatory decision making could reduce “cognitive capture” or “cultural capture”. (Needless to say all of these reforms have great intuitive appeal, but like campaign finance reforms, cry out for evidence from where similar are now implemented.) Teles does not mention campaign finance reform at all. I wondered whether this was a critique by omission, and found A New Agenda for Political Reform by Teles and Lee Drutman. They consider attempts to get money out of politics and increase participation to have largely failed and to have poor prospects, and argue the essential reform is to give the U.S. Congress more resources. Conclusion:

Convincing Congress, especially this Congress, to invest in its own staff capacity clearly won’t be easy. But neither is it inconceivable. Even small-government conservatives are feeling pressure to do something about the influence of corporate lobbying. Improving congressional capacity is a reform action they can take that would increase their own power, wouldn’t force them to agree with liberal get-the-money-out-of-politics types, and wouldn’t directly cross the corporate lobbying community. For those concerned about the malign influence of corporate power on our democracy, increasing government’s in-house nonpartisan expertise is almost certainly a more promising path forward than doubling down on more traditional reform strategies.

In Republic, Lost Lessig mentions many of the reforms that Teles writes about, and clearly considers dependence on fundraising concentrated money to be the essential blocker and first reform. I don’t know which is “right”. They largely see the same problems of a government controlled by concentrated interests. To the charge of failure and poor prospects above, I imagine that people like Lessig and Overton would respond that they have moved beyond getting money out of politics to getting more diverse money into politics, and beyond getting people to vote and somehow pay attention to getting them to feel more committed through making small and well matched donations. Presumably both sets of reforms are complementary, except to the extent they compete for reform attention.

This brings us to why I don’t like the referendum candidacy, where the referendum aims to fix the “rigged” system, and the referendum candidate resigns as soon as the bill intended to fix the system is passed. Many reforms are needed to fix the system, including those mentioned by Teles, and probably a selection of reforms favored by people who are committed to reducing wealth inequality as well as the power of government in some dimensions. In order to make the first reform resilient, further strengthening of governing and regulating institutions will have to be made, and the context of inequality and arbitrary power changed. Cursory reading of histories of empires in periods of decline show patriotic (in the sense described at the top) reform attempts, occasionally met with a bit of success, but quickly lost. Why would the American empire be any different? There’s no reason to think it might be other than patriotic (in the bad sense) delusion. If a candidate like Lessig were to get a mandate for reform, I’d want them to see it through. Passing one bill to de-concentrate campaign funding might be the necessary first reform, but I can’t see it being sufficient even to ensure the survival of itself, uncorrupted.

The Lessig referendum candidacy’s one bill includes more than a measure to de-concentrate campaign funding though. This measure is bundled with two others (voting rights and election method and districting reforms) under the name Citizen Equality Act. There is perhaps a hint of this in Republic, Lost, where equality of voting is mentioned, but in contrast to the inequality of campaign funding rather than as something needing reform. Now surely there are useful reforms to be made in these areas which would get closer to every voter having equal weight, in terms of access to voting and impact of their votes. But what happened to the one essential reform that must happen before any other than be achieved, uncorrupted? It’s there of course, but why have it share the focus with two good but non-blocking reforms? Here’s what I imagine: concern about inequality bubbles to the top of mainstream discourse, Lessig thinks that he’s got to connect with the equality movement, and comes up with the brand and bundling of “Citizen Equality”. Or maybe campaign finance reform was deemed to be not enough to base on referendum candidacy on, even though it is claimed to be the essential first reform. I have no idea how the Citizen Equality idea came about…but maybe it is a good one. Anti-corruption measures, especially as Lessig defines corruption, seem to largely be consequentialist: we can’t get nice things from a corrupt system (and if one is not careful, anti-corruption measures can be rights violating, even if they achieve good things on net). Voter equality measures on the other hand, seem largely to be about rights: the rights of individual voters, and the ability of minority groups to have a voice through the ballot and protect their rights from the majority. I imagine (surely this is something that has been studied in depth, but I am ignorant) that consequence and rights arguments appeal differently to different voters; a proposal which appeal to both could have better chances of acceptance.

Before closing I have to comment on a few bits pertinent to knowledge policy found in Republic, Lost:

Consider, for example, the case of movies. Imagine a blockbuster Hollywood feature that costs $20 million to make. Once a single copy of this film is in digital form, the Internet guarantees that millions of copies could be accessed in a matter of minutes. Those “extra†copies are the physical manifestation of the positive externality that a film creates. The value or content of that film can be shared easily—insanely easily—given the magic of “the Internets.â€

That ease of sharing creates risk of underproduction for such creative work: If the only way that this film can be made is for the company making it to get paid by those who watch it, or distribute it, then without some effective way to make sure that those who make copies pay for those copies, we’re not going to get many of those films made. That’s not to say we won’t get any films made. There are plenty of films that don’t exist for profit. Government propaganda is one example. Safety films that teach employees at slaughterhouses how to use dangerous equipment is another.

But if you’re like me, and want to watch Hollywood films more than government propaganda (and certainly more than safety films), you might well be keen to figure out how we can ensure that more of the former get made, even if we must suffer too much of the latter.

The answer is copyright—or, more precisely, an effective system of copyright. Copyright law gives the creator of a film (and other art forms) the legal right to control who makes copies of it, who can distribute it, who displays it publicly, and so forth. By giving the creator that power, the creator can then set the price he or she wants. If the system is effective, that price is respected—the only people who can get the film are the people who pay for it. The creator can thus get the return she wants in exchange for creating the film. We would be a poorer culture if copyright didn’t give artists and authors a return for their creativity.

I realize this just serves as an example in the context of Republic, Lost, but it’s an appallingly bad one. What risk of underproduction? What does that even mean in the context of entertainment? People love whatever culture they’re immersed in. Individuals have limited attention, massively over-saturated by a huge market. Private tax collection by copyright holders is not the only way to get films made; film making is hugely subsidized (even in the U.S., through location rent seeking), those subsidies could obtain films not subject to private enforcement of speech restrictions. Safety films and government propaganda as the examples of what would be produced without copyright? For government (in particular military/security state) propaganda — watch Hollywood. When not under the influence of offering explanations of how Hollywood blockbusters justify copyright, Lessig and the like celebrate the extraordinary creativity of non-commercial video artists of many forms, uploading countless hours of film superior to safety instruction and propaganda videos. Now presumably there would be many fewer Hollywood-style blockbusters without copyright (incidentally I think a zero was left off the cost figure in the quote, though much of that may be marketing). But a poorer culture? A somewhat different culture, certainly — one in which private censors are not empowered to damage the net, one in which monopoly knowledge rents do not concentrate cultural power, increase wealth inequality, and exclude the poorest from access to knowledge. I don’t expect Lessig to become a copyright abolitionist, and in any case think it is far more useful to advocate for commons-favoring policy than against copyright. But granting the commanding heights of culture wholesale to the copyright industry and narrowing the vision of what the commons can produce is no way to argue for any sort of reform, other than the sort the copyright industry wants.

Elsewhere in the book:

As with any speech regulation, the first question is whether there are other, less restrictive means of achieving the same legislative end. So if Congress could avoid dependence corruption by, say, funding elections publicly, that alternative would weaken any ability to justify speech restrictions to the same end. The objective should always be to achieve the legitimate objectives of the nation without restricting speech.

Apply this to the ends of entertainment production.

This seems like a good juncture to mention a related question: why not free political speech from private censorship? All political speech (by some definition, preferably all speech…but presumably speech paid for by campaign contributions) should be in the public domain. I doubt this would have any significant impact on campaigns or fundraising, but more freedom of speech, especially political speech, seems independently worthy.

A briefer and less bad mention of patents:

Those patents are necessary (so long as drug research is privately financed), but there has long been a debate about whether they get granted too easily, or whether “me-too†drugs get protection unnecessarily.

This seems to be another odd case in which an writer grants more necessity to copyright for entertainment production and less imagination for an alternative than for patents and drug development. Though I’m glad to see the parenthetical above (of course it ought be noted that public money already pays for much of the research, and buys much of the product…), I find the ordering bizarre. The piece I’ve seen similar but even more pronounced recently in is Teles’ The Scourge of Upward Redistribution!

From the “Conventional Game” and “Choosing Strategies” chapters:

These four reasons all point to a common lesson in the history of warfare: You don’t beat the British by lining up in red coats and marching on their lines, as they would on you. You beat them by adopting a strategy they’ve never met, or never played. The forces that would block this bill work well and effectively on Capitol Hill, and inside the Beltway. That is their home. And if we’re going to seize their home, and dismantle it, we need a strategy that they’re sure is going to fail. Yet we need it to win.

…

Insurgent movements have to fight the war on unconventional turf. If the issue gets decided finally within institutions that depend upon things staying the same, things will stay the same. But if we can move the battle outside the Beltway, to venues where the status quo has no natural advantage, then even small forces can effect big change.

These are exactly why in the space of knowledge policy that commons-based products and commons-favoring policy are so potent, and ought be taken as the primary mechanism of knowledge policy reform. Uncorrupted direct reform of copyright and patents (the standard menu includes things like reducing term lengths and increasing ‘quality’) probably is hopeless without de-concentrating funding of political campaigns (or whatever anti-corruption measure turns out to be the essential first step). Good luck to Lessig. In the meantime, knowledge commons can slowly (far too slowly now, I admit) change the structure of the knowledge economy, create concentrated interests that benefit from commons-favoring policy, and increase policy imagination for what is possible without intellectual property.

…

I started off claiming that Lessig is the most patriotic candidate for U.S. temporary dictator because he’s the only one putting his preferred issues to the side to fix the institutions of government and make collective action work better. But I have to admit that jingoist patriots (those with some patience anyway) ought also favor Lessig, because those are the qualities that give a nation the capacity to dominate others over the long term, if its constituents have such ugly desires.

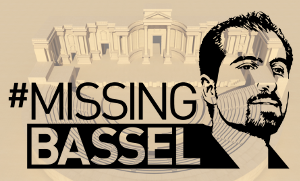

I’m helping organize a book titled “The Cost of Freedom” in honor of Bassel Khartabil, a contributor to numerous free/open knowledge projects worldwide and in Syria, where he’s been a political prisoner since 2012, missing and in grave danger since October 3. You can read about Bassel at https://www.eff.org/offline/bassel-khartabil

I’m helping organize a book titled “The Cost of Freedom” in honor of Bassel Khartabil, a contributor to numerous free/open knowledge projects worldwide and in Syria, where he’s been a political prisoner since 2012, missing and in grave danger since October 3. You can read about Bassel at https://www.eff.org/offline/bassel-khartabil