“Copyright” (henceforth, copyrestriction) is merely a current manifestation of humanity’s malgovernance of information, of commons, of information commons (the combination being the most pertinent here). Copyrestriction was born of royal censorship and monopoly grants. It has acquired an immense retinue of administrators, advocates, bureaucrats, goons, publicists, scholars, and more. Its details have changed and especially proliferated. But its concept and impact are intact: grab whatever revenue and control you can, given your power, and call your grabbing a “right” and necessary for progress. As a policy, copyrestriction is far from unique in exhibiting these qualities. It is only particularly interesting because it, or more broadly, information governance, is getting more important as everything becomes information intensive, increasingly via computation suffusing everything. Before returning to the present and future, note that copyrestriction is also not temporally unique among information policies. Restriction of information for the purposes of control and revenue has probably existed since the dawn of agriculture, if not longer, e.g., cults and guilds.

Copyrestriciton is not at all a right to copy a work, but a right to persecute others who distribute, perform, etc, a work. Although it is often said that a work is protected by copyrestriction, this is strictly not true. A work is protected through the existence of lots of copies and lots of curators. The same is true for information about a work, i.e., metadata, e.g., provenance. Copyrestriction is an attack on the safety of a work. Instead, copyrestriction protects the revenue and control of whoever holds copyrestriction on a work. In some cases, some elements of control remain with a work’s immediate author, even if they no longer hold copyrestriction: so-called moral rights.

Copyrestriction has become inexorably more restrictive. Technology has made it increasingly difficult for copyrestriction holders and their agents to actually restrict others’ copying and related activity. Neither trend has to give. Neither abolition nor police state in service of copyrestriction scenarios are likely in the near future. Nor is the strength of copyrestricition the only dimension to consider.

Free and open source software has demonstrated the ethical and practical value of the opposite of copyrestriction, which is not its absence, but regulation mandating the sharing of copies, specifically in forms suitable for inspection and improvement. This regulation most famously occurs in the form of source-requiring copyleft, e.g., the GNU General Public License (GPL), which allows copyrestriction holders to use copyrestriction to force others to share works based on GPL’d works in their preferred form for modification, e.g., source code for software. However, this regulation occurs through other means as well, e.g., communities and projects refusing to curate and distribute works not available in source form, funders mandating source release, and consumers refusing to buy works not available in source form. Pro-sharing regulation (using the term “regulation” maximally broadly to include government, market, and others; some will disbelieve in the efficacy or ethics of one or more, but realistically a mix will occur) could become part of many policies. If it does not, society will be put at great risk by relying in security through obscurity, and lose many opportunities to scrutinize, learn about, and improve society’s digital infrastructure and the computing devices individuals rely on to live their lives, and to live, period.

Information sharing, and regulation promoting and protecting the same, also ought play a large role in the future of science. Science, as well as required information disclosure in many contexts, long precedes free and open source software. The last has only put a finer point on pro-sharing regulation in relation to copyrestriction, since the most relevant works (mainly software) are directly subject to both. But the extent to which pro-sharing regulation becomes a prominent feature of information governance, and more narrowly, the extent to which people have software freedom, will depend mostly on the competitive success of projects that reveal or mandate revelation of source, the success of pro-sharing advocates in making the case that pro-sharing regulation is socially desirable, and their success in getting pro-sharing regulation enacted and enforced (again, whether in customer and funding agreements, government regulation, community constitutions, or other) much more so than copyrestriction-based enforcement of the GPL and similar. But it is possible that the GPL is setting an important precedent for pro-sharing regulation, even though the pro-sharing outcome is conceptually orthogonal to copyrestriction.

Returning to copyrestriction itself, if neither abolition nor totalism are imminent, will humanity muddle through? How? What might be done to reduce the harm of copyrestriction? This requires a brief review of the forces that have resulted in the current muddle, and whether we should expect any to change significantly, or foresee any new forces that will significantly impact copyrestriction.

Technology (itself, not the industry as an interest group) is often assumed to be making copyrestriction enforcement harder and driving demands for for harsher restrictions. In detail, that’s certainly true, but for centuries copyrestriciton has been resilient to technical changes that make copying ever easier. Copying will continue to get easier. In particular the “all culture on a thumb drive” (for some very limited definition of “all”) approaches, or is here if you only care about a few hundred feature length films, or are willing to use portable hard drive and only care about a few thousand films (or much larger numbers of books and songs). But steadily more efficient copying isn’t going to destroy copyrestriction sector revenue. More efficient copying may be necessary to maintain current levels of unauthorized sharing, given steady improvement in authorized availability of content industry controlled works, and little effort to make unauthorized sharing easy and worthwhile for most people (thanks largely to suppression of anyone who tries, and media management not being an easy problem). Also, most collection from businesses and other organizations has not and will probably not become much more difficult due to easier copying.

National governments are the most powerful entities in this list, and the biggest wildcards. Although most of the time they act roughly as administrators or follow the cue of more powerful national governments, copyrestriction laws and enforcement are ultimately in their courts. As industries that could gain from copyrestriction grow in developing nations, those national governments could take on leadership of increasing restriction and enforcement, and with less concern for civil liberties, could have few barriers. At the same time, some developing nations could decide they’ve had enough of copyrestriction’s inequality promotion. Wealthy national governments could react to these developments in any number of ways. Trade wars seem very plausible, actual war prompted by a copyrestriction or related dispute not unimaginable. Nations have fought stupid wars over many perceived economic threats.

The traditional copyrestriction industry is tiny relative to the global economy, and even the U.S. economy, but its concentration and cachet make it a very powerful lobbyist. It will grab all of the revenue and control it possibly can, and it isn’t fading away. As alluded to above, it could become much more powerful in currently developing nations. Generational change within the content industry should lead to companies in that industry better serving customers in a digital environment, including conceivably attenuating persecution of fans. But it is hard to see any internal change resulting in support for positive legal changes.

Artists have always served as exhibit one for the content industry, and have mostly served as willing exhibitions. This has been highly effective, and every category genuflects to the need for artists to be paid, and generally assumes that copyrestriction is mandatory to achieve this. Artists could cause problems for copyrestriction-based businesses and other organizations by demanding better treatment under the current system, but that would only effect the details of copyrestriction. Artists could significantly help reform if more were convinced of the goodness of reform and usefulness of speaking up. Neither seems very likely.

Other businesses, web companies most recently, oppose copyrestriction directions that would negatively impact their businesses in the short term. Their goal is not fundamental reform, but continuing whatever their current business is, preferably with increasing profits. Just the same as content industries. A fundamental feature of muddling through will be tests of various industries and companies to carve out and protect exceptions. And exploit copyrestriction whenever it suits them.

Administrators, ranging from lawyers to WIPO, though they work constantly to improve or exploit copyrestriciton, will not be the source of significant change.

Free and open source software and other constructed commons have already disrupted a number of categories, including server software and encyclopedias. This is highly significant for the future of copyrestriction, and more broadly, information governance, and a wildcard. Successful commons demonstrate feasibility and desirability of policy other than copyrestriction, help create a constituency for reducing copyrestriction and increasing pro-sharing policies, and diminish the constituency for copyrestriction by reducing the revenues and cultural centrality of restricted works and their controlling entities. How many additional sectors will opt-in freedom disrupt? How much and for how long will the cultural centrality of existing restricted works retard policy changes flowing from such disruptions?

Cultural change will affect the future of copyrestriction, but probably in detail only. As with technology change, copyrestriction has been incredibly resilient to tremendous cultural change over the last centuries.

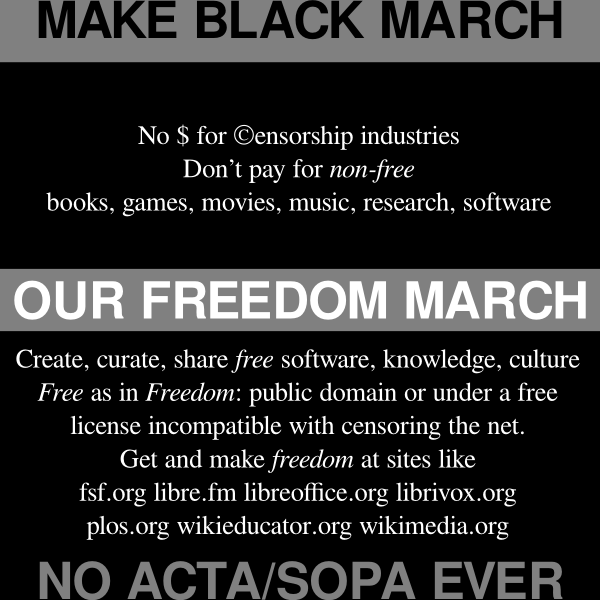

Copyrestriction reformers (which includes people who would merely prevent additional restrictions, abolitionists, and those between and beyond, with a huge range of motivations and strategies among them) will certainly affect the future of copyrestriction. Will they only mitigate dystopian scenarios, or cause positive change? So far they have mostly failed, as the political economy of diffuse versus concentrated interests would predict. Whether reformers succeed going forward will depend on how central and compelling they can make their socio-political cause, and thus swell their numbers and change society’s narrative around information governance — a wildcard.

Scholars contribute powerfully to society’s narrative over the long term, and constitute a separate wildcard. Much scholarship has moved from a property- and rights-based frame to a public policy frame, but this shift as yet is very shallow, and will remain so until a property- and rights-basis assumption is cut out from under today’s public policy veneer, and social scientists rather than lawyers dominate the conversation. This has occurred before. Over a century ago economists were deeply engaged in similar policy debates (mostly regarding patents, mostly contra). Battles were lost, and tragically economists lost interest, leaving the last century’s policy to be dominated by grabbers exploiting a narrative of rights, property, and intuitive theory about incentives as cover, with little exploration and explanation of public welfare to pierce that cover.

Each of the above determinants of the future of copyrestriction largely hinge on changing (beginning with engaging, in many cases) people’s minds, with partial exceptions for disruptive constructed commons and largely exogenous technology and culture change (partial as how these develop will be affected by copyrestriction policy and debate to some extent). Even those who cannot be expected to effect more than details as a class are worth engaging — much social welfare will be determined by details, under the safe assumption that society will muddle through rather than make fundamental changes.

I don’t know how to change or engage anyone’s mind, but close with considerations for those who might want to try:

- Make copyrestriction’s effect on wealth, income, and power inequality, across and within geographies, a central part of the debate.

- Investigate assumptions of beneficent origins of copyrestriction.

- Tolerate no infringement of intellectual freedom, nor that of any civil liberty, for the sake of copyrestriction.

- Do not assume optimality means “balance” nor that copyrestriction maximalism and public domain maximalism are the poles.

- Make pro-sharing, pro-transparency, pro-competition and anti-monopoly policies orthogonal to above dimension part of the debate.

- Investigate and celebrate the long-term policy impact of constructed commons such as free and open source software.

- Take into account market size, oversupply, network effects, non-pecuniary motivations, and the harmful effects of pecuniary motivations on creative work, when considering supply and quality of works.

- Do not grant that copyrestriction-based revenues are or have ever been the primary means of supporting creative work.

- Do not grant big budget movies as failsafe argument for copyrestriction; wonderful films will be produced without, and even if not, we will love whatever cultural forms exist and should be ashamed to accept any reduction of freedom for want of spectacle.

- Words are interesting and important but trivial next to substance. Replace all occurrences of “copyrestriction” with “copyright” as you see fit. There is no illusion concerning our referent.

This work takes part in the Future of Copyright Contest and is published under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.