Evan Prodromou just published his Federated Social Web top 10 stories of 2010. It’s a great list, go read — readers who aren’t already familiar with Prodromou, StatusNet, identi.ca, OStatus, etc. probably will have missed many of the stories — and they’re extremely important for the long-term future of the web, even if there are presently far too few zeros following the currency symbol to make them near-term major news (just like early days of the web, email, and the internet).

I suggest the following additions.

Censorship of dominant non-federated social web sites (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, YouTube) occurred around the world. While totally reprehensible, and surely one of the top social web stories of 2010 by itself, one of its effects makes it a top story for the federated social web — decentralization is one of the ways of “routing around” censorship. I’d love to have mountains more evidence, but perhaps this is happening.

Perhaps Evan did not want to self-promote in his top 10, but I consider the status of his company, its services, the software they run (all called StatusNet), and the community around all three, to be extremely important data points on the status of the federated social web, and thus inherently top stories for 2010 (and they will be again in 2011, even if they completely fail, which would be a sad top story).

I hope that Evan/StatusNet post their own 2010 summary, or the community develops one on the StatusNet wiki, but very briefly: The company obtained another round of funding and from the perspective of an outsider, appears to be progressing nicely on enterprise and premium hosting products. The StatusNet cloud hosts thousands of (premium and gratis) instances, and savvy people are self-hosting, mirroring the well-established wordpress.com/WordPress pattern. The core StatusNet software made great strides (I believe seven 0.9.x releases), obtained an add-ons directory, and early support for non-microblogging features, e.g., social bookmarking and generic social networking (latter Evan did mention as a non-top-10 story; of course any such features are federated “for free”). By the way, see my post Control Yourself, Follow Evan for the beginning story, way back in 2008.

2010 also saw what I consider disappointments in the federated social web space, each of which I have high hopes will be corrected in the next year — perhaps I’ll even do something to help:

StatusNet lacks full data portability and account migration.

Nobody has yet taken up the mantle of building a federated replacement for Flickr.

Unclear federated social web spam defenses are good enough.

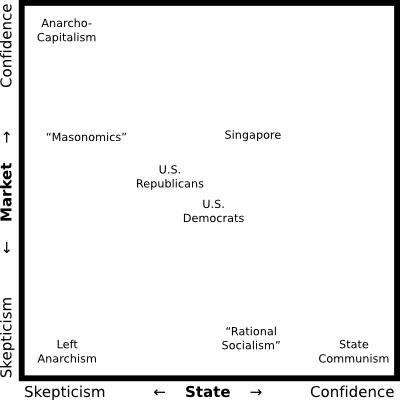

Nobody is doing anything interesting with reputation on the federated social web — no, make that, on the social web. This is a major befuddlement I’ve had since Friendster (2002), at least. SixDegrees had an excuse as the first “social network”, Advogato (1999) innovated, then nothing. Nothing!

Far too few people are aware of the challenges and opportunities of maintaining and expanding software freedom/user autonomy in the age of networked services, a general problem of which the federated social web is an important case.

Finally, a couple not-yet-stories for the federated social web.

Facebook and Twitter (especially Facebook) seem to have consolidated their dominant positions in nearly every part of the world, having surpassed regional leads of the likes of Orkut (Brazil and India), Bebo (UK), MySpace (US), Friendster (Southeast Asia), etc. and would-be competitors such as shut down (e.g., Jaiku and Plurk) or considered disappointing (e.g., Google Buzz). However, it seems there are plenty of relatively new regionally-focused services, some of which may already be huge but under the radar of English-speaking observers. An example is Weibo, Sina.com’s microblogging service, which I would not have heard of in 2010 had I not seen it in use at Sharism Forum in Shanghai. It’s possible that some of these are advantaged by censorship of global services — see above — and cooperation with local censors. Opportunity? Probably only long-term or opportunistic.

Despite their high cultural relevance and somewhat ambiguous status, I don’t know of many © disputes around tweets, or short messages generally. Part of the reason must be that Twitter and Facebook are primarily silos, and use within those silos is agreed to via their terms of service. I’m very happy that StatusNet has from the beginning take precaution against copyright interfering with the federated case — notices on StatusNet platforms are released under the permissive Creative Commons Attribution license (all uses permitted in advance, requiring only credit), which clarifies things to the extent copyright restricts, and doesn’t interfere to the extent it doesn’t. (Also note that copyright is a major challenge for the social web in general, even its silos — see YouTube, which ought be considered part of the social web.)

All the best to Evan Prodromou and other federated social web doers in 2011!

As demonstrated above, I cannot write a short blog post, which puts a crimp on my blogging. Follow me on StatusNet’s identi.ca service for lots of short updates.