Democracy and Decision, a 1993 book by economist/philosopher Geoffrey Brennan and political philosopher Loren Lomasky, undermines a relatively little known (to me) side of public choice theory–the assumption that voters vote in accordance with their (instrumental) interests.

Democracy and Decision, a 1993 book by economist/philosopher Geoffrey Brennan and political philosopher Loren Lomasky, undermines a relatively little known (to me) side of public choice theory–the assumption that voters vote in accordance with their (instrumental) interests.

The authors make a convincing case that because an individual voter is essentially never decisive, the rational voter will vote expressively, even if the vote that gains the voter the highest expressive value would be against the voter’s instrumental interests, if the voter were decisive. The authors summarize their proposition as “Rational action ⇠psuedorational voting.”

The following rendition of Table 2.2. Electoral choice as a quasi-prisoners’ dilemma (p. 28) illustrates a simple case where voters will vote according to their expressive values and against their instrumental values, as their probability of casting a decisive vote approaches nil.

| |

All others |

| Each |

Majority for a |

Majority for b |

Tie (probability → 0) |

| Vote for a |

5 |

105 |

5 |

| Vote for b |

0 |

100 |

100 |

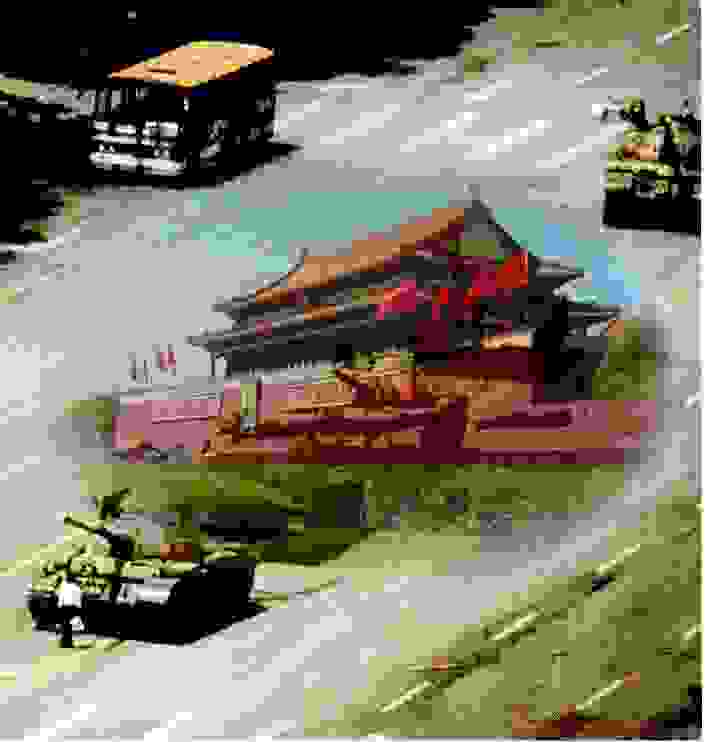

The authors make a reasonable case that voters’ instrumental and expressive values often are divergent. War seems to be a particularly strong case (p. 50):

How is it, then, that such mammoth exercises in irrationality seem to have been pursued so vigorously and with such popular enthusiasm in this most democratic of ages? The voters’ dilemma provides a possible explanation. Consider the individual voter contemplating a vote between competing political candidates in a setting where international relations are tense. One candidate offers a policy of appeasement, recognizing the enormous cost in lives and resources that any antagonistic stance might involve. the other candidate stands for national integrity — “By God, we are not going to be pushed around by these bastards.” We might well presume that few voters, making a careful calculation of the costs and benefits to themselves and those they care about, would actually opt for war. Just as individuals, in situations of interpersonal strain, will often swallow their pride, shrug their shoulders, and stroll off rather than commit themselves to an all-out fight (particularly one that might imply someone’s death), so the interest of most voters would be better served by drawing back from the belligerent course. Yet a careful reflective computation of the costs and benefits of the alternative outcomes to herself (and those others relevant to her concerns) is precisely what the voter does not entertain: Any such computation is essentially irrelevant. What is relevant, we might suppose, is the opportunity to show one’s patriotism, one’s antipathy to servility, one’s strength of national purpose.

Of course expressive preferences may be for peace instead. In either case, and for any issue, the main point is that “it will be the symbolic power of the policy rather than the costs and benefits the policy scatters on particular voters that will be most relevant.” (p. 51, emphasis in original)

A chapter is devoted to the probability that a vote is decisive–roughly speaking, the probability an election is decided by one vote, given an odd number of votes. It turns out the calculation of this probability is not straightforward, but any reasonable attempt seems to result in an infinitesimal value.

Strategic voting and widespread belief in the wasted vote argument against voting for minor party candidates would seem to indicate that voters do not vote expressively (surely the proportion of voters who could increase their expressive returns by voting for a “third party” candidate is higher than the roughly one percent who actually do so in U.S. presidential elections). However, at least four non-instrumental factors explain strategic voting: established parties have economies of scale in advertising, rationally habitual voting, voting for a candidate’s top competitor may give the highest expressive returns if a voter’s primary expresive desire is to “boo” the candidate, and being seen as voting “responsibly” is itself an expressive return.

One possibility I believe the authors do not address is that voters may irrationally believe there is a significant probability that their votes may be decisive. After all, the probability calculation is not obvious, and people presumably have terrible intuitions about very large (or small) numbers. The only two small hints of voter irrationality I noticed were on page 121–some voters may be irrationally instrumental–and the following odd quote from page 171:

One who intends through his vote to bring about the election of candidate X is on all fours with someone who steps on a crack with the intention of thereby breaking his grandmother’s back. Irrespective of what they may believe they are doing, they are in fact not acting intentionally to secure favored outcomes.

The fundamental lesson of the domination of voters’ instrumental preferences by expressive preferences is that homo economicus is a poor model for voter behavior.

Another way to put this is to distinguish “p-preferences” (those expressed when voting) from “m-preferences” (market preferences, or those expressed when the actor is decisive). The authors then discuss “r-preferences” (outcomes an actor may prefer upon reflection, but finds himself unwilling to act upon, e.g., a glutton may reflectively prefer to refuse a third serving of cake, but not actually do so) and the related concept of merit goods, items underconsumed even in ideal markets.

Voting dominated by expressive preferences could lead to the political provision of merit goods. However, demerit goods could also be provided.

The authors close with an analysis of the constitutional implications of expressive voting, e.g., what does it mean for federalism, the secret ballot, or representative democracy? Nothing is said in this chapter that hasn’t been said countless times without the benefit of a theory of expressive voting.

At the top of this post I said that the assumption the assumption of instrumental voting by public choice theory is relatively unknown to me. My very uneducated summary of the insight of public choice can be summed up as “concentrated interests trump diffuse interests.” The reason I considered theories of voting unimportant in this context is that voters are obviously diffuse. In my mind, the concentrated interests are not voter blocs, but organizations that manage to overcome the obstacles to collective (political) action (e.g., individual corporations, trade groups, and unions) and politicians themselves. I’m not sure what, if any, impact expressive voting has on this side of public choice theory. One impact may be that expressive voting within organizations lowers the bar for collective action.

There’s more to be said about the book, particularly on merit goods and related subjects (but it’s been a few months since I read Democracy and Decision, and my grasp on the subtleties is fading fast) and much more on the implications of expressive preferences outside the context of electoral contests, a subject the authors explicitly do not cover.