As promised, my first annual thematic doubt post, expressing doubts I have about themes I blogged about during 2013.

Intellectual Freedom

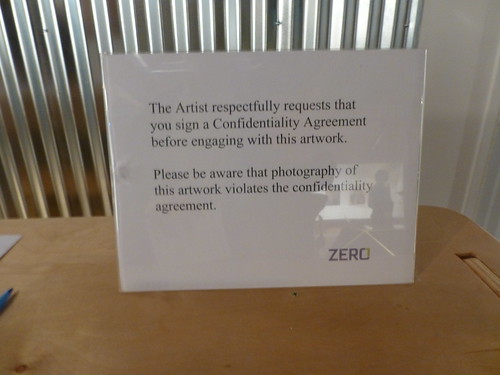

If this blog were to have a main purpose other than serving as a despository for my tangents, it’d be protecting and promoting intellectual freedom, in particular through the mechanisms of free/open/knowledge commons movements, and in reframing information and innovation policy with freedom and equality outcomes as top. Some representative posts: Economics and the Commons Conference [knowledge stream] report, Flow ∨ incentive 2013 anthology winner, z3R01P. I’m also fond of pointing out where these issues surface in unusual places and surfacing them where they are latent.

I’m fairly convinced on this theme: regimes infringing on intellectual freedom are individual and collective mind-rot, and “merely” accentuate the tendencies toward inequality and control of whatever systems they are embedded in. Mitigating, militating against, outcompeting, and abolishing such regimes are trivially for the good, low risk, and non-revolutionary. But sure, I have doubts:

- Though I see their accentuation of inequality and control as increasingly important, and high leverage for determining future outcomes, copyright and patent could instead be froth. The cause of intellectual freedom might be better helped by fighting for traditional free speech issues, for tolerance, against mass incarceration, against the drug war, against war, against corruption, for whatever one’s favored economic system is…

- The voluntarily constructed commons that I emphasize (e.g., free software, open access) could be a trap: everything seems to grow fast as population (and faster, internet population) grows, but this could cloud these commons being systematically outcompeted. Rather than being undersold, product competition from the commons will never outgrow their dwarfish forms, will never shift nor take the commanding heights (e.g., premium video, pharma) and hence are a burden to both policy and beating-of-the-bounds competition. Plus, copyright and the like are mind-rot: generations of commons activists minds have been rotted and co-opted by learning to work within protectionist regimes rather than fighting and ignoring them.

- An intellectual freedom infringing regime which produced faster technical innovation than an intellectual freedom respecting regime could render the latter irrelevant, like industrial societies rendered agricultural societies irrelevant, and agricultural societies rendered hunter-gatherer societies irrelevant, whatever the effects of those transitions on freedom and other values were. I don’t believe the current regime is anywhere close to being such a thing, nor are the usual “IP maximalism” reforms taking it in that direction. But it is possible that innovation policy is all that matters. Neither freedom and equality nor the rents of incumbents matter, except as obstacles and diversions from discovering and implementing innovation policy optimized to produce the most technical innovation.

I’m not, but can easily imagine being won over by these doubts. Each merits engagement, which could result in much stronger arguments for intellectual freedom, especially knowledge commons.

Critical Cheering

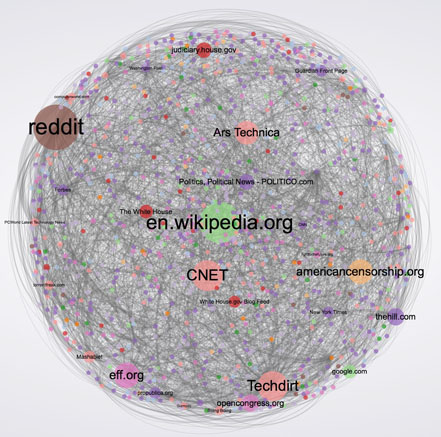

Unplanned, unnoticed by me until late in the year, my most pervasive subtheme was criticism-embedded-in-praise of free/open/commons entities and actions. Representative posts, title replaced with main target: Creative Commons, crowdfunding, Defensive Patent License, Document Freedom Day, DRM-in-HTML5 outrage, EFF, federated social web, Internet Archive, Open Knowledge Foundation, SOPA/ACTA online protests, surveillance outrage, and the Wikimedia movement.

This is an old theme: examples from 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2011, and 2012. 2009 and 2010 are absent, but the reason for my light blogging here bears some relation to the theme: those are the years I was, in theory, most intensely trying to “walk my talk” at Creative Commons (and mostly failed, side-tracked by trying to get the organization to follow much more basic best practices, and by vast amounts of silliness).

Doubts about the cheering part are implied in the previous section. I’ll focus on the criticism here, but cheering is the larger component, and real: of entities criticized in the above links, in 2013 I donated money to at least EFF, FSF, and Internet Archive, and uncritically promoted all of them at various points. The criticism part amounts to:

- Gains could be had from better coordination among entities and across domains, ranging from collaboration toward a short term goal (e.g., free format adoption) to diffuse mutual reinforcement that comes from shared knowledge, appreciation, and adoption of free/open/commons tools and materials across domains (e.g., open education people use open source software as inherent part of their practice of openness, and vice versa).

- The commons are politically potent, in at least two ways: minimally, as existence proof for creativity and innovation in an intellectual freedom respecting regime (carved out); and vastly underappreciated, as destroyer of rents dependent on the intellectual freedom infringing regime, and of resources available for defending those rents and the regime. Commons are not merely to be protected from further bad policy, but are actors in creating a good policy environment, and should be promoted at every turn.

To be clear, my criticism is not usually a call for more “radical” or “extreme” steps or messages, rather more fulsome and coordinated ones. Admittedly, sometimes it may be hard to tell the difference — and this leads to my doubts:

- Given that coordination is hard, gaining knowledge is expensive, and optimization path dependent, the entities and movements I criticize may not have room to improve, at least not in the direction I want them to improve in. The cost of making “more fulsome and coordinated” true might be greater than mutual reinforcement and other gains.

- See the second doubt in the previous section — competition from the commons might be futile. Rather than promoting them at every turn, they should sometimes be held up as victims of bad policy, to be protected, and sometimes hidden from policy discourse.

The first doubt is surely merited, at least for many entities on many issues. For any criticism I have in this space, it makes sense to give the criticized the benefit of the doubt; they know their constraints pretty well, while I’m just making abstract speculations. Still, I think it’s worthwhile to call for more fulsome and coordinated strategy in the interstices of these movements, e.g., conversation and even this blog, in the hope of long-term learning, played out over years in existing entities and movements, and new ones. I will try henceforth to do so more often in a “big picture” way, or through example, and less often through criticism of specific choices made by specific entities — in retrospect the stream of the latter on this blog over the last year has been tedious.

International Apartheid

For example: Abolish Foreignness, Do we have any scrap of evidence that [the Chinese Exclusion Act] made us better off?, and Opposing “illegal†immigration is xenophobic, or more bluntly, advocating for apartheid “because it’s the lawâ€. I hinted at a subtheme about the role of cities, to be filled out later.

The system is grossly unjust and ought be abolished, about that I have no doubt. Existing institutions and arrangements must adapt. But, two doubts about my approach:

- Too little expression of empathy with those who assume the goodness of current policy. Fear of change, competition, “other” are all deep. Too little about how current unjust system can be unwound in a way the mitigates any reality behind these fears. Too little about how benefits attributed to current unjust system can be maintained under a freedom respecting regime. (This doubt also applies to the intellectual freedom theme.)

- Figuring out development might be more feasible, and certainly would have more impact on human welfare, individual autonomy, than smashing the international apartheid system. Local improvements to education, business, governance, are what all ought focus on — though development economics has a dismal record, it at least has the right target. Migration is a sideshow.

As with the intellectual freedom theme, these doubts merit engagement, and such will strengthen the case for freedom. But even moreso than in the case of intellectual freedom infringing regimes, the unconscionable and murderous injustice of the international apartheid regime must be condemned from the rooftops. It is sickening and unproductive to allow discourse on this topic to proceed as if the regime is anything but an abomination, however unfeasible its destruction may seem in the short term.

Politics

Although much of what I write here can be deemed political, one political theme not subsumed by others is inadequate self-regulation of the government “market”, e.g., What to do about democratically elected terrorist regimes, Suppose they gave a war on terror and a few exposed it as terror, and Why does the U.S. federal government permit negative sum competition among U.S. states and localities?

The main problem with this theme is omission rather than doubt — no solutions proposed. Had I done so, I’d have plenty to doubt.

Refutation

I fell behind, doing refuting only posts from first and second quarters of 2005. My doubt about this enjoyable exercise is that it is too contrived. Many of the refutations are flippant and don’t reflect any real doubts or knowledge gained in the last 8 years. That doubt is what led me to the exercise of this post. How did I do?